I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.

I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.

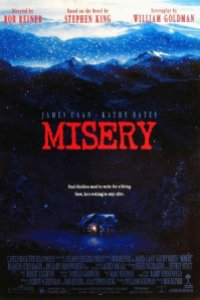

The film is famous for Kathy Bates’s marvelous ability to flip a switch between feelings of serendipity and sadism, but it never uses its full potential to explore the psychological realms of depth that must be going through these two characters’ heads.

The story is well-known, namely because it is a strong one, and “Misery” is nothing if not a well made, genre thriller. Paul Sheldon (James Caan), a famous author of trashy romance novels, gets into a nearly fatal car wreck and is rescued by his number one fan, Annie Wilkes (Bates). She nurses him back to health but makes clear before long that she will keep him in her small, reclusive home until he rectifies the troubling ending to his latest book.

But ultimately, this punishment is too one-dimensional. Paul has done nothing wrong, so this is not a morality tale. And Annie is just an insane serial killer with an unhealthy obsession. The movie doesn’t ask why she singled out Paul’s Misery novels, and it doesn’t even seem like she is some perverse mastermind with sinister motives to hold him there from the very beginning. She’s only driven by passion and nothing specific. I most wondered about the dinner scene where Paul attempts to poison Annie by pouring medicine in her wine. She spills her cup and pours a new glass, but was that an accident, or did she know what Paul was up to? The movie is vague, and never leads us to believe that Annie is anything more than what’s on the surface. It’s less Hitchcockian and more the story of someone trapped in an unfortunately macabre situation. Maybe that’s King-ian. I wouldn’t know.

I kept wanting to know what was going through Paul’s mind. We see him by himself a lot, but he doesn’t share his thoughts with us the way he might through internal monologues in a book. I would bet that being forced to write a new Misery novel after he has cast off the series would be some kind of torture, but the movie shows him cranking it out in a montage in a determined escape attempt.

Part of the reason I asked myself such questions is because Reiner’s camera forces us into a heightened sense of awareness from the get go. The film’s first shots are extreme close-ups of a cigarette and a bottle of champagne, and a simple Google search will show just how many starkly centered images of Bates’s face are everywhere. Except none of it has a deeper meaning. None of it clues in to suspense the way Hitchcock might with such blatantly obvious shots.

“Misery” doesn’t seem like it’s made by a man who is out of his element, even though Reiner’s previous films included the romantic comedies “The Princess Bride,” “The Sure Thing” and “When Harry Met Sally” and the fake rockumentary “This is Spinal Tap,” but he also doesn’t seem like the master director that would best fit a story as psychologically dense as King’s.