While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”.

While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”.

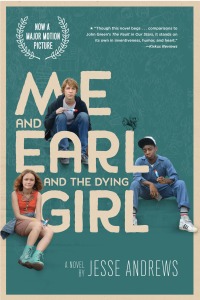

“Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” swept this year’s Sundance with not just the Grand Jury Prize but also the audience award. I expect it to be a massive mainstream hit. It would be so easy to lob one of those adjectives onto it and write it off as something less than a masterpiece because it falls into The Sundance Movie category.

And Alfonso Gomez-Rejon’s film all but announces that it will be that sort of movie in its opening moments: voice-over narration from a cynical teenager making wry observations and quoting pop culture, all based on a bestselling YA novel. But in just as quickly, Rejon makes waves with those expectations. “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” is dark, cringe-worthy, weird and best of all, cinematic. In its use of both film references and active cinematography, Rejon’s film is as much about cinema as it is adolescence. He’s playing with genres and expectations in a way that is so hilarious, heartwarming and utterly gratifying.

“Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” is one of those movies, but it is also un-ironically the best movie of the year.

The Me of “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” is Greg (Thomas Mann), a smart high school senior not lonely and misanthropic, and not trying to avoid human contact, but trying to avoid any serious connections. He latches onto individual cliques for just long enough to be acknowledged but not long enough to be labeled. He’s got it down to a science. While the narration is a common tool in this sort of indie, it’s the camera that really gets inside Greg’s mind. There’s a running gag involving stop-motion animation about how hot girls are like a moose stepping on a helpless squirrel, a gag that kills every time it abruptly makes an appearance. There’s even a hilarious shot in which Greg’s mom (Connie Britton) walks in on him as he’s looking at porn, and his frantic attempt to switch tabs only reveals more nudity.

His parents inform him that one of the girls in his class, Rachel (Olivia Cooke), is suffering from leukemia. Greg doesn’t really know her, and she insists she doesn’t need new friends or pity from someone being forced by their mom to come over, but then of course he was forced by his mom to spend time with her in the first place. “Eight years of carefully cultivated invisibility, gone,” he says.

Greg reveals to Rachel his affinity for making movies with his “coworker” Earl (RJ Clyer), a tough nosed kid from the other side of town. Their films are all horribly bad remakes, replacing one letter or word of a classic title to make it a potty-mouthed, so-dumb-it’s-awesome pun, and the results are a thing of beauty. Everything from “Apocalypse Now” to “Burden of Dreams” is skewered. It’s a film that goes deeper into cinephilia than most movies that claim to do the same. Soon the two find themselves making a film for Rachel, but Greg subconsciously feels doing so would allow him to get too close to someone so sick.

The story has the arc of something like last year’s “The Fault in Our Stars,” but the plot itself doesn’t even emerge until midway into the film. Rejon and Jesse Andrews’s screenplay, working from his own novel, find depth in their characters and allow them to emerge through conversation rather than situation comedy. It gets laughs because it isn’t afraid for Greg to put his foot in his mouth with an idiotic joke telling Rachel to play dead. It isn’t too cute to have Earl blurt out in his baritone voice “Titties” as soon as the thought crosses your mind. And it isn’t averse to having Nick Offerman shove a cat in the camera’s face.

There’s a healthy cynicism to everything here, and the movie literally turns on its head in a few moments to create an awareness of the camera and the cinematic devices at play. Like a Wes Anderson film, it’s extremely attentive to detail but without the artificiality that a handful find frustrating about Anderson’s style. Rejon finds beauty in static long takes, quick movement and even quicker editing, and time and again Greg steps out of his character’s shoes to explain to the audience things are not going to happen with the same melodrama or emotional catharsis you’d expect.

As a result, “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” goes from a fairly outrageous and unexpected comedy to getting very real, real fast. Rejon grapples with spiritual sensations of love and life after death, and he doesn’t forget that these adult themes are still filtered through the minds of teenagers. The film’s climax and ending scene in particular capture the same screwball charm but are moments of sensational beauty.

“Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” is a lot like its protagonist and his desire to stay on an island unto himself. It’s a comedy and a tearjerker, and it’s smart and cute and quirky, but it just touches on those qualities without ever belonging to a single group.

4 stars

Great review! I wasn’t sure about this film based on the trailer (and uncomfortable title), but I’m going to have to check this one out now 🙂