George Miller made a movie this year that is little but a chase scene, with themes of survival, revenge and a showcase for hyper violence and cinematic spectacle. The film has virtually no story, but the nature of its editing and its use of color, movement and staging made it an exhilarating experience, brutal and devastating but also cathartic and purely entertaining.

George Miller made a movie this year that is little but a chase scene, with themes of survival, revenge and a showcase for hyper violence and cinematic spectacle. The film has virtually no story, but the nature of its editing and its use of color, movement and staging made it an exhilarating experience, brutal and devastating but also cathartic and purely entertaining.

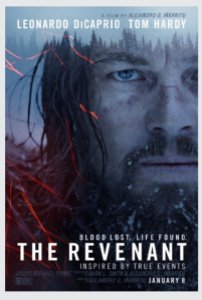

Alejandro G. Inarritu’s “The Revenant” is a similar revenge fantasy, stripped to its bones in all its animalistic nature and fury, but Emmanuel Lubezki’s cinematography blunts the impact. The Malick-esque way that Lubezki plays with the elements to create something spectral and naturalistic give “The Revenant” an overstated sense of importance, and watching it is hardly entertaining but dreary, disgusting and devoid of purpose.

Set in early frontier America, Leonardo DiCaprio plays Hugh Glass, a navigator part of a hunting party gathering pelts. Natives ambush the entire squadron and reduce the team from 45 people to just 10. The scene is ravishing, but immediately numbing. Arrows fly in and impale the Americans from beyond the frame, creating a sense early on that danger is not imminent but seemingly omnipresent. The mise-en-scene is cold and silvery and makes a stark backdrop for fiery streaks of arrows flying through the sky.

Lubezki has the camera dive underneath the water to witness one man being strangled to death, and we realize that despite the camera’s pivots and surveying, it’s more of a godly spectator rather than a human eye. The camera here is far less a gimmick than in Inarritu’s “Birdman,” and the way the camera is freed from a fixed axis is not unlike how Lubezki’s cinematography floated and tumbled in “Gravity.” But seeing it in this way isn’t visceral but bleak, violent, bloody and full of agony.

Glass escapes the natives only to be attacked by a bear. This scene too is an endless, torturous and dispassionate sight done in a single, unbroken shot. The bear claws and stomps on his back and whips him like a doll. It exists seemingly out of time and even ends on something of a grim punch line, a final knife in the back as Glass tumbles down a hill only for the slain bear to roll on top of him.

Miraculously, Glass survives, but just barely. Captain Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson) demands the remaining troop care for him and keep him alive as long as possible. When they’re unable to transport the wounded Glass further, Henry assigns John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) to tend to Glass and Glass’s half-breed son Hawk (Forrest Goodluck) until Glass dies. Instead, Fitzgerald kills Hawk and leaves Glass for dead. “The Revenant” starts as Glass’s fight for survival against nature, a cold look at how the world is vengeful and how the wilderness governs all. But it eventually morphs into a more simplistic revenge fantasy, Glass’s quest to return from the dead and kill the man who murdered his son.

We see flashes of Glass’s past, of his native bride being slaughtered and skulls being stacked high in a mountain. Except Glass’s remaining existence is no less bleak, and his past plays as a morbid form of adding insult to injury. He survives by eating hunks of bloody, raw buffalo meat and by cutting open the guts of a horse and crawling inside its open cavity for warmth. The film’s gore is disturbing, but the subject matter itself is not the problem. “Mad Max: Fury Road” was no less shocking, and even “Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back” involves Luke killing an animal for warmth on the ice planet Hoth.

The difference is how Inarritu lingers on the gruesomeness and screams each shot’s importance, not for their ingenuity but their stark reality. The score pounds with thundering drums that signal each moment’s weight, and the way “The Revenant” evokes God as a theme continually burdens us with the idea that this is Glass against the world.

DiCaprio is a victim of the film’s agony, grunting and moaning his way through the entire film and crawling on the cold ground for much of it. There’s only so much of an actual performance here. Tom Hardy is more effective as the dissenting and ruthless Fitzgerald, complete with a thick, broken Americana accent and wide eyes that show his madness.

While Lubezki remains the more interesting entry point to “The Revenant,” the blame for the movie’s depressing and exhausting slog rests on Inarritu’s shoulders. Like how the film treats Glass, he does all he can to drag us through hell but little catharsis or solace to bring us back.

1 ½ stars