Steve Jobs and Apple didn’t invent the personal computer. They didn’t invent the portable music player, or the smart phone, or the tablet, or most recently wearable tech. What Steve Jobs did was make technology inviting, accessible and fashionable. That was his innovation and his genius. And it’s something of a paradox that the most successful tech giant is not the one with the newest or the best technology, but the one that reaches its users personally.

Steve Jobs and Apple didn’t invent the personal computer. They didn’t invent the portable music player, or the smart phone, or the tablet, or most recently wearable tech. What Steve Jobs did was make technology inviting, accessible and fashionable. That was his innovation and his genius. And it’s something of a paradox that the most successful tech giant is not the one with the newest or the best technology, but the one that reaches its users personally.

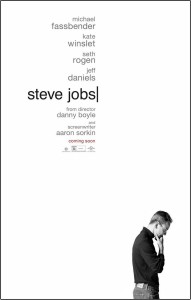

“Steve Jobs”, the new biopic directed by Danny Boyle and written by Aaron Sorkin, expertly plays on the conflict within Jobs’s embattled ideologies. Like Sorkin’s “The Social Network” before it, “Steve Jobs” goes beyond the notion that many great men have to step on others to get to the top. It reckons with the idea of being great and being a good person as two sides of the same coin. It enlists Apple veterans Steve Wozniak, John Sculley and Andy Hertzfeld to take up arms against Jobs’s deceptively flowery rhetoric and his vision of democratization. And yet the film’s style and staging presents a man still in the right, not just an asshole but the only asshole who saw the world in the right way.

Sorkin breaks “Steve Jobs” up into three chapters, each staged in real-time just minutes before the product launch of the Macintosh in 1984, the NeXT launch in the late ‘80s after Jobs was ousted from Apple, and finally in 1998 when he was brought back to unveil the iMac. Not only does the screenplay have an identical setting structure, Sorkin layers the narrative structure in a way that’s rife with narrative callbacks and payoffs. It’s excellent dramatizing, even if it largely stretches the truth of the 30-odd minutes between Jobs taking the stage.

One of the first things we hear Steve Jobs (Michael Fassbender) say is “Fuck You” when his programmer Andy Hertzfeld (Michael Stuhlbarg) says they can’t get the voice demo of the Macintosh speaking “Hello” to work. Boyle shoots the scene in a hazy, docu-realistic filter, and in this first moment looking down on Jobs from the fish eye of the projection screen above, it places Jobs at odds with the world. Immediately Sorkin makes the observation that though the Macintosh was made for “everybody”, the computer can only be opened up by special tools nowhere to be found in the building.

Both the operating system and the computer itself are closed off, incompatible with other products and unable to be customized, perhaps not unlike Jobs himself. And yet Jobs speaks with a vision of the computer’s personality and its ability to be a computer built around how people actually think. Fassbender has a way of delivering every line with a charismatic, uplifting and reassuring demeanor, even as he’s threatening and condescending. Always the PR mastermind, he expertly deflects his ex-wife’s (Katherine Waterston) question about how he feels about his daughter’s financial state of affairs by saying he believes Apple stock is undervalued. He promises to ruin Hertzfeld’s career if he doesn’t get the voice demo working, and he justifies it by saying with a wry snarl, “God sent his only son on a suicide mission, but we like him because he made trees!”

Each of the three segments involves Jobs coordinating with his weary and overworked micro-manager Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet), politely acknowledging the journalist Joel Pforzheimer (John Ortiz) and sparring and talking shop with his colleagues Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen) and John Sculley (Jeff Daniels). In each segment he’s running late to the stage, he confuses the names of two Andys who work for him, and he argues with his family before conceding to offer them whatever money they need. Jobs is of the sort who has to argue and get his perspective across, even if he decides to give in anyway.

You can see how “Steve Jobs” could function as a recurring Aaron Sorkin series, with repeating jokes and lines and enough walking and talking to fill an entire season of “The West Wing,” but Boyle places a certain rhythm to everything that allows each segment to flow fluidly.

Like Jobs, Danny Boyle is a showman. Rather than the tight, digital aesthetic that the previously attached David Fincher would’ve surely brought to the film, each of the three time periods looks aesthetically evolved from the next. The first is the gritty documentary-realism look, followed by a more operatic, artistic and colorful flavor, to finally the clean, luminous and familiar look of Apple’s brand today.

Boyle and Sorkin also have a good way of bringing the same gravity to early discussions about corporate and tech jargon to later conversations involving Jobs’s family melodrama. It eventually ups the stakes by taking the backstage conflict and putting it in the forefront, with Jobs and Wozniak screaming over the Apple 2 team right in front of the crowded hall of Apple employees. And for all of Jobs’s ability to quote Bob Dylan or speak the praises of Alan Turing, the film is at its best when a character like Jobs’s daughter can reduce his big ideas to the simplest of metaphors, like that the iMac really just looks like Judy Jetson’s Easy Bake Oven.

“Steve Jobs” is Sorkinesque beyond measure, but there’s nothing inherently wrong with Sorkin sticking to something that works, especially when the ensemble performances are as strong as they are here. Fassbender spars with everyone, and even when he loses his cool he never drops the air of greatness he carries on his shoulders, constantly defending his own greatness to anyone who would question it. Rogen graduates Woz from a playful pushover to a solemn and seasoned accomplice who has put up with Jobs’s insistence too many times. Winslet is another powerhouse, seeing through Jobs’s ideologies even as she looks tired and defeated by loyally and slavishly managing Jobs’s life. And Daniels is perfectly at home in Sorkin’s dialogue, with both he and Fassbender so wonderfully combative and fiery.

Steve Jobs has become such a revered fixture of the 21st Century that “Steve Jobs” has reignited discussions about the nature of accuracy in a biopic. It seemed easier to accept that Mark Zuckerberg might be an asshole, but is now harder to imagine that Jobs was anything of a contentious figure. Wozniak says near the end of the film that being a genius and being a good person is not binary. By bending the truth of Jobs’s personality and heightening a discussion around his ideologies, Sorkin’s script contends that in some ways it is.

4 stars