“Rear Window” has been mercilessly scrutinized, fitting for a movie about people obsessed with minute details. We fully understand how the movie is put together, how Alfred Hitchcock creates suspense minimally and how he ties all those tingling suspicions into a story of voyeurism, privacy, neighbors and curiosity.

But those who have seen the film will know how emotionally wrenching it is. Tangential to the main mystery, Hitchcock colors an entire community of lonely people struggling with marriages, romances or careers. These livelihoods serve not to add clues to the murder mystery but to emphasize the one core idea running through “Rear Window,” a fear that could be shared by anyone, not just Hitchcock: “What if you are witness to something terrible and can do nothing to prevent it?”

Poor L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart) is witness to a lot of such trauma, even within his own life. But as is true outside of the window, he’s pretty powerless to do anything about it. His romance with the wealthy and glamorous Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly) is troubled. The two of them are incompatible people, yet she’s clearly in love. He knows she’s perfect but can’t foresee a way to make it work, and she can’t do a thing to change his mind.

Grace Kelly doesn’t give the best performance of her career in “Rear Window,” but she has sad, sweet, authentic eyes that make the viewer fall in love with her and pity the thought that Jeff is such a stubborn mule. Even Jeff’s nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) can’t do much to help their cause, and beneath her snarky, comic relief attitude is a hint of melancholy as well.

But the stories of “Rear Window” that will stick with you more are the ones surrounding the central story and, conveniently, central apartment.

To one side of the courtyard is Miss Lonelyhearts, a middle aged woman looking for love and crying herself to sleep each evening. Before Jeff assigns her a nickname, we see her preparing a candlelit dinner and go through the motions of a date. Being distant from the actual event, we create little narratives about these people, and for a moment you suspect that she’s trying to make everything perfect before her date arrives. Alas, we then see her bury her head in her arms and pour herself a drink. The fact that we can’t know exactly how hurt she is makes us feel all the worse.

Then there’s the struggling songwriter, who writes a beautiful theme to color Jeff and Lisa’s evening, but can’t find a way to make a living off it. A party will later suggest that things are going his way, but then we seem to get a glimpse of him looking out his own window longingly wishing for a different outcome. How do we know all this from a few glimpses inside his apartment window? In a lot of ways we don’t, which makes this life too something of a mystery.

In another instance, Hitchcock shows us barely anything at all. A newlywed couple moves into an apartment across the way. The groom carries his bride over the threshold after the landlord has left, and they close the curtain and seem to be in love. When only the man appears at the window some days later, the dynamic seems to have changed. Whatever minimal body language he displays, things are not well in paradise.

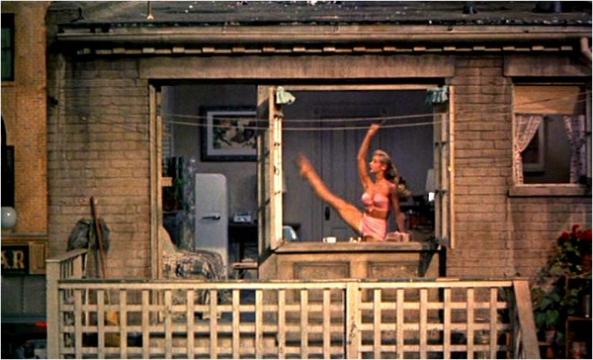

Last is the wonderfully named Miss Torso, a dancer with a killer body and a liberal way of parading in front of an open window. Her presence is immediately linked to the film’s voyeuristic ideas, and yet she too eventually functions as someone more than eye candy. Given the pick of the litter of wealthy suitors, Lisa senses that she’s in love with none of them after Jeff suggests that the two have similar apartments. It’s a wonderfully bittersweet moment that ties all of these emotions together.

Hitchcock isn’t usually so touchy-feely. And I’m overselling “Rear Window” a bit, having not even begun to describe the actual murder that makes it famous. After all, “Rear Window” was one of Hitchcock’s “successful experiments,” unlike something like “Vertigo,” which was seen as a flop on the time of its release.

But again differing from “Vertigo,” a movie that is deeply rooted in psychology, “Rear Window” views the psychological ideas of voyeurism on a surface level. The pathos at “Rear Window’s” root is a big part of what makes the film more than an experiment.

“Rear Window” is a good candidate not just for Hitchcock’s best but also Hitchcock’s most accessible for newcomers, and it’s because it’s a film that makes us feel as deeply as we are afraid.