Part way through “The Battle of Algiers” is a sequence in which Algerian locals perform quick, targeted assassinations on French officers throughout the region. One boy nonchalantly follows behind a policeman who suspects he’s up to no good. It’s a coincidence, the boy assures him, but the officer frisks him anyway. Satisfied to find nothing, he gets into a car, and the boy fishes a gun out of a nearby trash can and shoots him dead.

Resistance comes in many forms in “The Battle of Algiers,” and the interconnected methodology to each killing in this sequence seems like a precursor of the baptism montage at the end of “The Godfather.” Much has been made about Gillo Pontecorvo’s documentarian roots and this film’s modeling off news reels and ’60s doc realism, but that thread to New Hollywood makes it seem so much more modern.

Pontecorvo is constantly playing with intense close-ups, quick camera darts, rapid zooms and of course a stapled together editing style in which weeks pass by in a smash cut or the tides of war turn on a dime. To call it documentary realistic is accurate in the sense that it resembles news reels more than Old Hollywood, but the documentarians and found footage makers of today don’t credit as much to Pontecorvo’s political masterpiece. We see this film’s breadcrumbs on modern action movies and social cause movies all the way up to “Argo.”

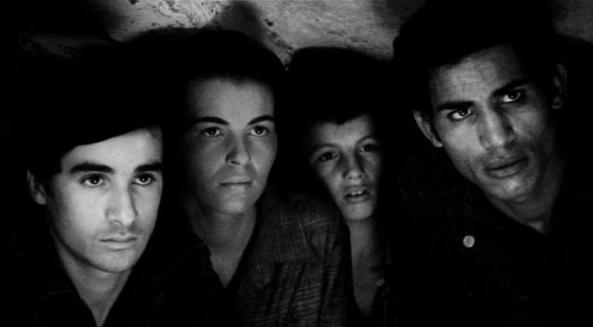

How otherwise would you explain the stylized emptiness of “The Battle of Algiers'” prologue, in which the hero Ali la Pointe finds himself trapped behind a wall with three of his young rebel associates, or when a man in prison is beheaded and the film strings together blink-or-you’ll-miss canted angles of the lonely prison walls and the sound of the guillotine reverberating off them?

“The Battle of Algiers” is a film about propoganda, control and authority. Why appears to be in power is the group that’s really winning. Pontecorvo discusses politics indirectly, like with a French colonel who allows the press to interview a captured Algerian terrorist and poses to the French journalists the question, “should France be in Algeria?” “If the answer is yes, you must accept all the consequences ” But the film shines more prominently when a young boy steals a microphone for a PA system and covertly announces to a gathering of Algerians that the rebellion FLN is in fact in control.

This is an action movie yes, but it has a poignant core that truly makes it a masterpiece. The FLN has enlisted three women to plant bombs in dense French regions of Algiers. They’re fair skinned and pretty and get by checkpoints without inspection. When they arrive at their destinations, the camera surveys the room and finds friendly patrons, smiling children and frolicking, dancing teens. Revolution is important, but it comes at a price for both sides. That’s the most modern sentiment of all.