Critics who today bristle at true movie spectacles like “Avatar” or “Gravity” for want of a more substantive story are less likely to do the same when faced with a silent film. The technical precision and thoughtful filmmaking required to communicate ideas and tell any story seems to be enough.

Critics who today bristle at true movie spectacles like “Avatar” or “Gravity” for want of a more substantive story are less likely to do the same when faced with a silent film. The technical precision and thoughtful filmmaking required to communicate ideas and tell any story seems to be enough.

And yet “The Thief of Bagdad” is pure spectacle, lacking the psychological heft of “Metropolis”, the emotional beauty of “Sunrise”, the economic and timeless genius of Buster Keaton stunts, but it rivals all of them and more as a film full of real movie moments. The production design is grand and daunting, the creativity and scope is unmatched. It is not a “film” but a “movie” with inspiration and sights worthy of a prince.

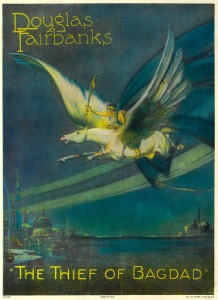

Such was the nature of the swashbuckler film, a genre of capes and swords and heroes and sandals in a far off Eastern World and period in history. None were better than “The Thief of Bagdad”, and no one was a bigger star than Douglas Fairbanks Sr. His visage here is rugged, shirtless, masculine, cocky and virile. Fairbanks opens the film sleeping in the sun in the busy Baghdad bazaar, awaiting unsuspecting citizens to stop to take a drink so he can swipe their purses. Despite his crimes, Fairbanks immediately carries the movie star swagger that would define onscreen masculinity for decades. He’s the film’s hero because we know him to be. And his charms as a thief and criminal, one tempted to drug the princess, one who is sacrilegious and rejects God, are shocking and remarkable for a pre-code film.

But there’s no sense what he’s doing is wrong. It’s fun and exciting action of a man on the run. One of the film’s great early stunts sees him throw a man’s turban onto a high-up ledge, place it beneath the man’s heavy frame, tie the end to a donkey, and get the motion of the donkey to lift him up.

Fairbanks did all his own stunts, and despite having his hands in every aspect of the film, he stayed out of the way to allow Raoul Walsh to direct and capture the moment in one perfect wide shot. And Fairbanks makes it look easy, performing with a wink and a smirk much unlike the stone-faced Keaton when doing the same.

Truly though “The Thief of Bagdad’s” charms are in the effects and spectacle and not the stunts alone. The film was the first to cost over $1 million. Though that’s just $13 million in today’s dollars, hardly enough for even a mid-size indie, Fairbanks orchestrated upwards of six acres on which to build his Baghdad, staging magnificent palaces and armies of extras to populate this miniature city. And the money is certainly on the screen. We see tigers and chimps climbing out of trap doors, massive and ornate palace gates opening in sections, hazy, glimmering filters to create underwater sequences, hidden caves and valleys of fire, many with vast depth in the shots to highlight the film’s grandiose proportions.

Admittedly these effects have not aged well, or perhaps are not as timeless as some of the more tangible effects in other silent classics. Fairbanks does battle with a monster that’s in actuality a superimposed reptile with additional spikes. He rides a “Winged Horse” that doesn’t fly but gallops “in the sky”. And yet to see Fairbanks and the princess take off on a flying carpet at the end of the film is as whimsical as advertised.

The story is drawn from the tales of Arabian Nights legend, and was remade most notably in 1940, another fantasy classic. Modern audiences however might know it best as Disney’s “Aladdin”. A thief living on the streets makes to steal treasure from the palace, but encounters the princess and falls in love. She is to be wed to one of several princely suitors (“He’s fat and gross as if fed on lard!”), so the thief disguises himself as a prince to win her affection. When he is outed as a fraud, he goes on a quest to find a magic chest that will make him a prince, all while the evil Mongol prince plots to capture Baghdad.

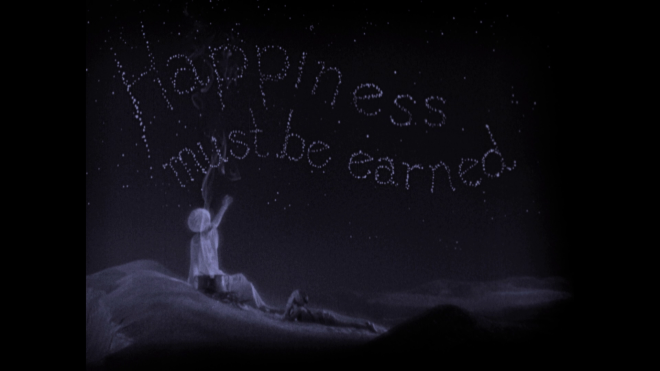

It’s a charming tale of romance, adventure and all that makes a great swashbuckler, even if it does greatly sag during the more modest scenes of romance. But “The Thief of Bagdad” is ultimately a spiritual journey. The film is bookended with the priest’s prophecy, “Happiness Must Be Earned.” The effort on splendor on display here is more than enough to earn any modern audience’s happiness.