Gene Siskel would always ask, “Is this film more interesting than a documentary about how it was made?”

Such has been the guiding logic with “Hearts of Darkness,” a documentary on the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” The production hell this film went through is still unrivaled in terms of sheer difficulty and complexity, and some would argue (see: recent episode of “Community”) that the telling of such an immense story actually surpasses Coppola’s masterpiece. “Hearts of Darkness” stands for the same themes of surreal unpredictability and radical change of perspective that “Apocalypse” is about, and it is mystifying and immersive in the way it engages us with such powerful, conflicting emotions.

And yet, you likely couldn’t make a documentary as interesting as this if the subsequent film weren’t also fairly interesting. The Coppola we see has mixed feelings about his film, viewing it as a potential masterpiece with ambitions that are so great and tell so much, and yet he knows that achieving such a vision on film is virtually impossible. Almost never throughout the course of filming is Coppola completely satisfied with his actors, his sets or his own words. He hates the ending most of all, and he said as much at Cannes. Here he calls it too macho an ending, and something closer to the novel would have been more appropriate.

But he never quits in filming. The artwork is done in the process, and it is a never ending process. The art doesn’t stop when the cameras cut. Anyone working that tirelessly and following along with the art at every stage of its development could drive a person insane. But he boldly asserts that you must act as if you are going forward and finishing whatever you’ve claimed, even if it turns into a vanity project that only answers questions for you. They’ll call it pretentious, and that’s what all filmmakers fear, but if it can’t even answer questions for him, then what good is it?

Coppola’s experience in the woods and swamps of the Philippines to make his Vietnam War epic changed his worldview, but perhaps the finished product of his film never answered the questions he sought. Thankfully, “Apocalypse Now” is hardly pretentious.

Director Fax Behr constructs a story from Eleanor Coppola’s documentary footage that truly gets at Francis’s psychological complexity. It’s a chronological retelling of the over 200 days they spent filming, beginning with the origins of “Heart of Darkness” as a film. Orson Welles wanted Joseph Conrad’s novel to be his first film. When the budget was too vast, he made “Citizen Kane” instead.

Coppola tried again before making “The Godfather,” but no studio wanted to deal with the ties to Vietnam. The script was again shelved for years. But after the success of both “Godfather” films, he had directorial freedom and financed $13 million himself. After 10 days of filming, he made the first hard choice and fired his then lead actor, Harvey Keitel, replacing him with Martin Sheen. Sheen was so much his character that it altered his personality. He later suffered from a severe heart attack and was read his Last Rites by a non-English speaking priest.

Coppola also juggled a collaboration with the Philippine military, his $1 million contract with an overweight, difficult and unprepared Marlon Brando, a typhoon that killed 200 local residents and the construction of a massive temple with the help of hundreds. The Gods seemed to be against this film, and Coppola’s hubris flied in his undying defiance to it all.

He really does not come across as entirely rational or sympathetic here. His requirements for a scene inside a luxuriously dream like French home (later cut from the theatrical version, but now available on Redux) sound petty when he requires that red wine be served at 58 degrees, and when all of the things that would make it perfect are not met, he shows his true personal anger and frustration.

“Hearts of Darkness’s” behind the scenes moments are so evocative of “Apocalypse Now,” such as in the caribou slaughter scene or in the infamous shot of a flair being shot high into the dark sky, and yet some of it can seem self-indulgent, complex and vague without meaning or direction. These feelings are perversions of themselves. They conflict at every turn, and so do the ambitions of “Apocalypse Now.” It’s a miracle of embattled ideas and personalities.

What’s impossible to now know is the media firestorm that circled around this project in the 1970s. Today, news would have spread much quicker, been much more fierce and may have killed the project sooner, but Coppola’s fiasco was unheard of. He was not a David Lean, Alfred Hitchcock or Cecil B. Demille. He was a new kid on the block, even if he had won Oscars just before, and this smacked of pretension beyond any.

This film also helped spread misleading rumors about the “actual ending” to the film, in which it is believed that in another version, Kurtz’s entire complex explodes. A still of this image exists in the credits of “Apocalypse Now,” and this film has marvelous footage of the actual set being demolished, but it was merely a necessity captured on film and not scripted.

“Apocalypse Now” is a masterpiece. It is one of my all-time favorites, but could it really be were it not for all this struggle? Often it is true that from great pain or great passion springs great art, and “Hearts of Darkness” embodies all the love and rage that went into this miracle of cinema.

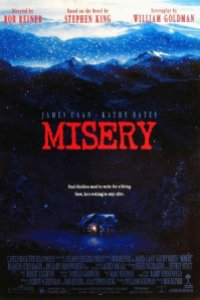

I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.

I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.