With “Midnight Special,” Jeff Nichols’s fourth film (“Mud, “Take Shelter”), Nichols remains the best emerging American director today, capable of infusing any genre with earthy, Americana trappings and unpacking the intimate character drama within. “Midnight Special” channels sci-fi, noir and family melodrama in unpredictable, startling ways and resembles a modern day stab at the personal conflict of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or the spirituality of “Contact.”

With “Midnight Special,” Jeff Nichols’s fourth film (“Mud, “Take Shelter”), Nichols remains the best emerging American director today, capable of infusing any genre with earthy, Americana trappings and unpacking the intimate character drama within. “Midnight Special” channels sci-fi, noir and family melodrama in unpredictable, startling ways and resembles a modern day stab at the personal conflict of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or the spirituality of “Contact.”

Except the story of “Midnight Special” defies easy classification and blends genres with thrilling results. At its very core a chase film, “Midnight Special” begins with Roy (Michael Shannon) on the run for having abducted a young boy named Alton Meyer (Jaeden Lieberher). He and a former cop named Lucas (Joel Edgerton) are trying to get Alton to an undisclosed location while evading a religious cult who sees Alton as their savior and the FBI who believes Alton knows confidential government information. Roy however is really Alton’s birth father, separated from him by the cult leader Calvin Meyer (Sam Shepard).

Above the sci-fi tension and conspiracy theories, the father-son dynamic between Alton and Roy truly drives “Midnight Special.” Alton possesses untold powers that change and grow more intense and severe the more they remain unchecked, from being able to unconsciously tap into radio frequencies to locking eyes with powerful blue tractor beams of light. Roy can’t fully comprehend all that’s happening to Alton, covering his eyes with blue swim goggles and transporting him only at night, but he displays a need to protect him above any greater cause the boy might represent to the cult or to the government.

As a result, Shannon proves a touching father figure. His eyes and body language are more muted and less intense than in many of his other fiery roles, but he’s gruff and a man of few words in a way that will be familiar to many fathers and sons. “I like worrying about you. I’ll always worry about you Alton. That’s the deal,” he says. All this family drama weaves wonderfully within “Midnight Special’s” denser scientific jargon and spiritual underpinnings. The ambiguous nature of Alton’s abilities and ties to another world all serve the film’s mystery and suspense.

And “Midnight Special” is highly entertaining and beguiling. Nichols seeps the film in darkness and other-worldly lens flares. The quiet, procedural and noir-like filmmaking make Alton’s skills all the more startling when the fireworks begin. “Midnight Special” even has a sense of humor. Adam Driver (“Girls,” “The Force Awakens”) as the NSA analyst tracking Alton is out of place in the best way possible. He has an awkward, nerdy charm that’s practically foreign to the more rural sensibilities of the rest of the cast.

With “Midnight Special” Nichols has proven that he can take a larger budget and still deliver the intimate character drama of an indie. As a director and screenwriter, Nichols has as much untapped potential as Alton.

4 stars

Have blockbusters really come to this? We’ve grown so desperate to make superheroes dark, gritty and realistic that we’ve fallen to sticking Superman, in full spandex, in front of Congress? “Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice” has it all: senatorial hearings, editorial newsroom meetings, CNN, Charlie Rose? It’s the spectacle of the new millennium!

Have blockbusters really come to this? We’ve grown so desperate to make superheroes dark, gritty and realistic that we’ve fallen to sticking Superman, in full spandex, in front of Congress? “Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice” has it all: senatorial hearings, editorial newsroom meetings, CNN, Charlie Rose? It’s the spectacle of the new millennium! “The Hunting Ground,” Kirby Dick’s documentary about sexual assault on college campuses across America, recognizes there is a major, widespread problem in this country when it comes to rape. Dick makes an effort to serve all those survivors affected. No instance of rape is too small.

“The Hunting Ground,” Kirby Dick’s documentary about sexual assault on college campuses across America, recognizes there is a major, widespread problem in this country when it comes to rape. Dick makes an effort to serve all those survivors affected. No instance of rape is too small. The opening moments of the Oscar nominated Netflix documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?” are so volatile and unpredictable in a way that captured Nina Simone’s musical essence, and it’s a shame director Liz Garbus can’t harness that lightning in a bottle throughout the rest of her film. It becomes a far more conventional musical biography told in relative chronological order, but is still entertaining and revealing about this influential musician’s life.

The opening moments of the Oscar nominated Netflix documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?” are so volatile and unpredictable in a way that captured Nina Simone’s musical essence, and it’s a shame director Liz Garbus can’t harness that lightning in a bottle throughout the rest of her film. It becomes a far more conventional musical biography told in relative chronological order, but is still entertaining and revealing about this influential musician’s life. I don’t mean to diminish the “mumblecore” movement of films – although I suspect if you dislike the lot of them outright you won’t find much to sway you in “Results” – but while Andrew Bujalski’s latest has been described by critics as a move toward a more traditional rom-com, it’s a perfect example of how mumblecore can drag down a perfectly acceptable genre film.

I don’t mean to diminish the “mumblecore” movement of films – although I suspect if you dislike the lot of them outright you won’t find much to sway you in “Results” – but while Andrew Bujalski’s latest has been described by critics as a move toward a more traditional rom-com, it’s a perfect example of how mumblecore can drag down a perfectly acceptable genre film. In ways that are both enlightening and maddening, Terrence Malick continues to demonstrate in his latest film “Knight of Cups” a remarkable eye for visuals and creative ways of playing with depth. Since “

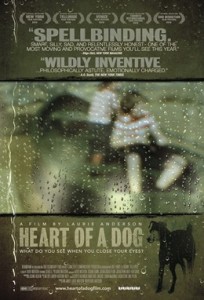

In ways that are both enlightening and maddening, Terrence Malick continues to demonstrate in his latest film “Knight of Cups” a remarkable eye for visuals and creative ways of playing with depth. Since “ It’s been argued that the most experimental films are often the most realistic. In Laurie Anderson’s touching, lovely, thoughtful and spiritual visual essay “Heart of a Dog,” she approximates the inner workings of the mind through her language, animation and sound. Between delightfully twee anecdotes and more melancholy meditations on life, Anderson grapples with the notions of death and loss and goes deeper into these subjects than most traditionally fictional stories.

It’s been argued that the most experimental films are often the most realistic. In Laurie Anderson’s touching, lovely, thoughtful and spiritual visual essay “Heart of a Dog,” she approximates the inner workings of the mind through her language, animation and sound. Between delightfully twee anecdotes and more melancholy meditations on life, Anderson grapples with the notions of death and loss and goes deeper into these subjects than most traditionally fictional stories. J.J. Abrams projects tend to be more interesting as viral marketing campaigns than as actual films. Not so with “10 Cloverfield Lane,” a tightly-wound chamber drama and horror thriller that bares ties to the 2007 surprise blockbuster “Cloverfield” in name only.

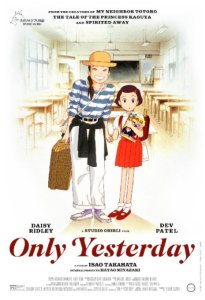

J.J. Abrams projects tend to be more interesting as viral marketing campaigns than as actual films. Not so with “10 Cloverfield Lane,” a tightly-wound chamber drama and horror thriller that bares ties to the 2007 surprise blockbuster “Cloverfield” in name only. Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

“Embrace of the Serpent” mysteriously and surreally takes us on a journey through nature and history to examine the value of preserving culture in the face of radical, profound change. Told in two time periods surrounding the Amazonian shaman Karamakate’s encounters both as a young and old man with visiting white men, Ciro Guerra’s Oscar nominated foreign language film finds unexplored twists in the culture clash narrative and delivers an entrancing look at the jungle through a native’s eye.

“Embrace of the Serpent” mysteriously and surreally takes us on a journey through nature and history to examine the value of preserving culture in the face of radical, profound change. Told in two time periods surrounding the Amazonian shaman Karamakate’s encounters both as a young and old man with visiting white men, Ciro Guerra’s Oscar nominated foreign language film finds unexplored twists in the culture clash narrative and delivers an entrancing look at the jungle through a native’s eye.