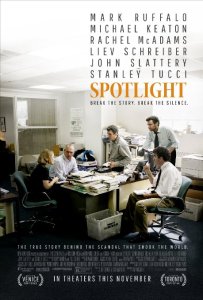

Name me another music biopic that opens with a battering ram. “Straight Outta Compton’s” incredible sense of location is so strongly of the streets and of the Compton neighborhood. It knows how crazy things can get, to the point where it needs to begin with the cops bringing an army to nail some black kids doing drugs. Director F. Gary Gray places the film not in the canon of other music biopics but in the league of a racially charged masterpiece like “Boyz n the Hood” or “Friday,” which Gray also directed starring N.W.A’s Ice Cube.

Name me another music biopic that opens with a battering ram. “Straight Outta Compton’s” incredible sense of location is so strongly of the streets and of the Compton neighborhood. It knows how crazy things can get, to the point where it needs to begin with the cops bringing an army to nail some black kids doing drugs. Director F. Gary Gray places the film not in the canon of other music biopics but in the league of a racially charged masterpiece like “Boyz n the Hood” or “Friday,” which Gray also directed starring N.W.A’s Ice Cube.

The music of N.W.A. and specifically the album “Straight Outta Compton” is so charged with personality and local identity that it would be a mistake if the movie didn’t also aim for that level of knowledge about the community in which it was brought up. These kids starting out making music show some real effort in a tough upbringing, and their attitude is to rap about that reality. “Speak a little truth and people lose their minds,” the film says, and we can see how immediately crazy things can get. The words matter more than the beats, and the movie doesn’t over intellectualize their music to the point of fawning over its brilliance. It just scares the shit out of people, leaving room for some truly insane rock star moments, like a massive hotel orgy culminating in N.W.A. pulling out their massive glocks at some intruders like it was nothing.

But on a biopic level, “Straight Outta Compton” is rare in how it manages an effective, yet comprehensive story. The film starts with N.W.A. cutting their first single and goes until Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins), Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson Jr.) and Easy-E (Jason Mitchell) had all gone their separate solo routes. With the Director’s Cut at nearly 3 hours, it takes its time fleshing out the story of all three characters individually, rather than trying to stuff subplots into the story of one. I imagine it’s how a Beatles biopic would have to be approached were anyone to ever take it on.

“Straight Outta Compton” even plays the biopic game of showy musical performances and celebrity cameos, but embedded within each of these more superfluous set pieces and attractions is a real sense of danger. The cops could be harassing the band or Suge Knight could be threatening to shoot a crewmember in the next room. Paul Giamatti is also officially the go-to guy as a sleazy, manipulative tour manager, having now played the part here, in “Rock of Ages” and “Love & Mercy.”

Music biopics are often concerned with history and personal legacy, but Gray makes “Straight Outta Compton” modern and urgent in its delivery of powerful melodrama, vital lyrics and hyper-relevant themes. This is a Movie With Attitude.

3 ½ stars

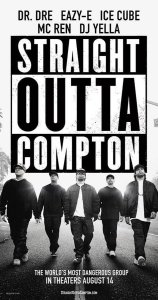

When Amy Winehouse passed away, the cruel and obvious joke of people reciting, “They tried to make me go to rehab, and I said no, no, no” was repeated on end. She even fit into the superstition of The 27 Club, young artists like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain who all died far too early in their prime. These labels put her into easy boxes, and her music and her personality was never easy to classify.

When Amy Winehouse passed away, the cruel and obvious joke of people reciting, “They tried to make me go to rehab, and I said no, no, no” was repeated on end. She even fit into the superstition of The 27 Club, young artists like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain who all died far too early in their prime. These labels put her into easy boxes, and her music and her personality was never easy to classify.

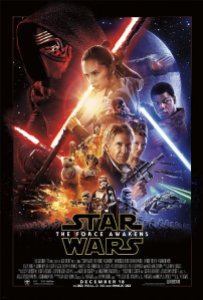

I was 9 years old when “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace” was released, and despite all the bile hurled at the prequels, at that age I had no concept of good. All I knew was that there was more. More Star Wars was a good thing, and for the Millennials like me who give the prequels the most hatred, “Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens” is the first Star Wars movie we’ve been able to see for the first time as adults.

I was 9 years old when “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace” was released, and despite all the bile hurled at the prequels, at that age I had no concept of good. All I knew was that there was more. More Star Wars was a good thing, and for the Millennials like me who give the prequels the most hatred, “Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens” is the first Star Wars movie we’ve been able to see for the first time as adults. How do you have a Hunger Games movie without the Hunger Games? That was essentially the problem of “

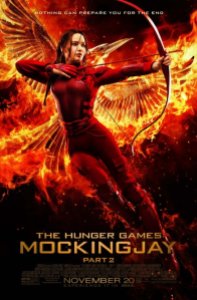

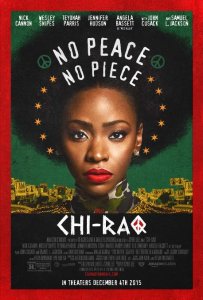

How do you have a Hunger Games movie without the Hunger Games? That was essentially the problem of “ No movie this year is as bold-faced opinionated and timely of a political statement as Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq.” That’s because movies are rarely this topical, this aggressive or this urgent. The film is littered with names of African Americans the media has been shouting for months, it has numerous hashtag ready catch phrases, it stops the film for a sermon that is essentially a vicious op-ed, and it declares up front that “This is an EMERGENCY” in giant, flashing red letters.

No movie this year is as bold-faced opinionated and timely of a political statement as Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq.” That’s because movies are rarely this topical, this aggressive or this urgent. The film is littered with names of African Americans the media has been shouting for months, it has numerous hashtag ready catch phrases, it stops the film for a sermon that is essentially a vicious op-ed, and it declares up front that “This is an EMERGENCY” in giant, flashing red letters.

No filmmaker is more of a modern day Fellini than Italian auteur Paolo Sorrentino. His films are opulent wonders, but while his extravagant visual style has for some become a sensory overload, it was Sorrentino reckoning with that same opulence in his last film, the Oscar winning foreign language film “

No filmmaker is more of a modern day Fellini than Italian auteur Paolo Sorrentino. His films are opulent wonders, but while his extravagant visual style has for some become a sensory overload, it was Sorrentino reckoning with that same opulence in his last film, the Oscar winning foreign language film “ Rooney Mara as Therese Belivet in Todd Haynes’s “Carol” has perky, rosy makeup, frayed bangs beneath a plain black hair band, cute plaid outfits and a checkered fall hat. She looks like one of the toy dolls in the department store where she works. Enter Cate Blanchett as Carol Aird, who wears a movie star aura with a giant coat of golden fur, a stylish red French cap and later in the car an elegant green shawl to keep her looking perfect.

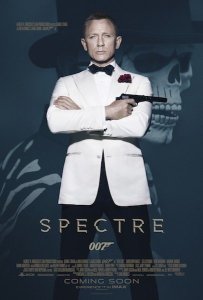

Rooney Mara as Therese Belivet in Todd Haynes’s “Carol” has perky, rosy makeup, frayed bangs beneath a plain black hair band, cute plaid outfits and a checkered fall hat. She looks like one of the toy dolls in the department store where she works. Enter Cate Blanchett as Carol Aird, who wears a movie star aura with a giant coat of golden fur, a stylish red French cap and later in the car an elegant green shawl to keep her looking perfect. Do we need James Bond in 2015? After 2013’s incredible “

Do we need James Bond in 2015? After 2013’s incredible “