It’s hard to imagine a time now when Woody Allen was not a legend, when he was just a comic appearing on talk shows and “What’s My Line” and making completely ridiculous screwball comedies free of any Oscar pedigree.

But this is the period in the ’70s when Allen was at the top of his game. His two films just before his first masterpiece, “Annie Hall,” were two genre spoofs that, as Roger Ebert said in his review, cemented Allen at the top of comedic directors of the time, ousting even the less prolific Mel Brooks.

These two films are “Sleeper” and “Love and Death,” both of which I watched yesterday. To see the two films together is to realize how similar they are and yet how much they vary from some of his more personal and dramatic work to come later in his career.

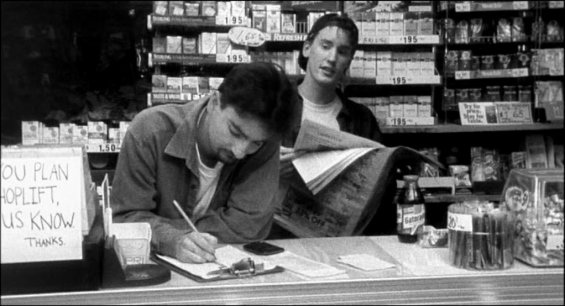

“Sleeper” is an ingenious sci-fi farce about the owner of a health food store in 1973 Greenwich Village who wakes up 200 years in the future after never waking up following a simple ulcer operation. He plays much of the early sequences straight and allows himself to morph into a Marx Brother or Buster Keaton sitting in the midst of all this cosmic nonsense. Doctors pull foil off his face to reveal that he’s been wearing his glasses the entire time, and the fourth wall is instantly broken.

We get funny details about the future like how tobacco is actually the healthiest thing for your body, as are fatty foods, both completely opposite of what they believed in 1973. But Allen takes it a step further when they ask him to identify certain historical relics from his time. With a completely straight face he misleads them because, well what’s the difference anyway? “This is Bela Lugosi. he was, he was the mayor of New York city for a while, you can see what it did to him there, you know. This is, uhm, this is, uh, Charles DeGaulle, he, he was a very famous French chef, had his own television show, showed you how to make souffles and omelets and everything.”

“Sleeper” has an outrageous sitcomy premise that forces him to pose as a robot and as a doctor performing a cloning operation, and his slapstick and chemistry with Diane Keaton (who is likewise brilliant, at one point performing a hammy Marlon Brando in “Streetcar” with the utmost charm) is as good as most Chaplin or Groucho Marx.

But Allen adds something more to the comic hysteria. The film’s color palette makes it resemble a ’70s New Age bohemian lifestyle shot in an expansive style reminiscent of Kubrick, with Keaton’s oblivious character acting no better than a spoiled socialite and then a pseudo-intellectual activist. He makes no real attempt to hide the fact that his sci-fi is a blatant comedic allegory about the ridiculous notions of society he’s living in 1973.

And it’s a riot. He’s got as many great one liners as ever and just as many completely goofy sight gags. The orgasmatron. A robot dog. Two Jewish robots in a clothing store. Cops who can never seem to work their high-tech weaponry. “The NRA? It was a group that helped criminals get guns to shoot citizens.” “I believe that there’s an intelligence to the world with the exception of certain parts of New Jersey.” “I’m 237 years old. I should be collecting social security.” “Has it really been 200 years since you had sex? 204 if you count my marriage.”

I could go on, but I have another movie to talk about yet.

“Love and Death” pulls a similar gag as “Sleeper” by putting a modern day character in a completely fish-out-of-water scenario, this time 19th Century Russia to poke fun at stuffy costume dramas. With this film he is again toying with the conventions and cliche of a genre, not adhering to the storytelling rules like in a Mel Brooks comedy but kind of just going through the motions to allow for more punch lines.

Allen plays Boris, a cowardly peasant forced to fight in a war against Napoleon, only to miraculously survive and return a war hero. He sleeps with a voluptuous countess and is challenged to a duel he’s sure to lose. Anticipating his death, he confesses his love for Sonja (Keaton) and she agrees to marry him out of pity in certainty he’ll lose. Soon they grow to love each other anyway and plan to assassinate Napoleon by impersonating Spanish royalty.

All of these story lines are tropes of some Leo Tolstoy novel or something, but Allen glosses over them in musical montages. He introduces an African American drill sergeant, he exaggerates profound soliloquies into meaninglessly poetic monologues and he finds room for a few more vaudeville-esque slapstick routines.

He’s so obvious about how he’s poking fun at all these cliches that the actual wit and charm doesn’t come out as strongly. It’s a bit of a cheesier execution that also doesn’t get across Allen’s two cents as strongly in the end. But he has a lot of fun here, and the movie has its own aesthetic charms that a Mel Brooks film might lack.

What I noticed about Woody Allen in this period is that he plays a character in much the same way Chaplin or Keaton did. It’s an extension of himself and ultimately synonymous with him, but he is acting. In “Sleeper” he seems to play the part of the neurotic coward to get out of assisting in a government revolution he has no care for. We know he has a backbone somewhere. And that’s because in both films he’s somehow an alluring sexual figure, capable of effortlessly seducing women because he exists in the modern day and not in this fantasy he’s constructed.

This is the opposite of how Diane Keaton acts. In both films she’s a loose sex symbol, sleeping around with multiple guys and emanating an innocent verve as she does. It’s a perfect screen persona she shares with Allen, one that allows her to be lovable and yet cynically funny. It’s a far throw from Mia Farrow’s surly character in another Woody Allen spoof, “Broadway Danny Rose.”

Now I find it hard to watch both of these films and not watch “Annie Hall” next, so maybe expect a classics piece on that in just a few days.