Oh, I miss movies like “Face/Off.” We still have “John Wick” and “Kingsman” and “Mad Max: Fury Road,” sure, but superheroes and perhaps the dark and gritty brand of Christopher Nolan movies have made the truly ridiculous action movie an endangered species and a thing of the past.

Oh, I miss movies like “Face/Off.” We still have “John Wick” and “Kingsman” and “Mad Max: Fury Road,” sure, but superheroes and perhaps the dark and gritty brand of Christopher Nolan movies have made the truly ridiculous action movie an endangered species and a thing of the past.

It was a different time, the ’90s. Pokemon may be back, but the superficially stupid and one-dimensional movies that un-ironically shoved explosions in our faces got replaced in favor of more serious fare. “Face/Off” was the most bananas of them all, and you could say that movies like “Face/Off” disappeared because everything was trying to be “Face/Off.” We have hordes of “Die Hard” copycats and directors pretending to be Quentin Tarantino, but people could only dream that their films could be as stylized as John Woo’s, and as insane as his stories.

Much of that success has to do with Nicolas Cage being on the best role of his life. After winning an Oscar for “Leaving Las Vegas,” he chose to follow that up by claiming the action hero belt away from the Stallones and Schwarzeneggers, starring in “The Rock,” “Con Air” and “Face/Off” within a little over a calendar year. All three were major blockbusters.

Cage plays Castor Troy, who plants a bomb in the LA Convention Center dressed as a dancing terrorist minister. He waltzes over to a singing choir sporting a devilish grin and sneaks a squeeze of a choir girl’s butt, experiencing ecstasy as he does. “You know, I can eat a peach for hours,” he says with a menacing smile. He wields a pair of gold pistols, he flashes his teeth wildly, whips off his sunglasses to make eye contact with the camera.

And then after getting captured by his FBI rival Sean Archer (John Travolta), who seeks revenge after Troy killed Archer’s son, the two switch faces. I repeat: they exchange ‘effing faces.

“John Wick” and others may be stylish, brutal and simplistic, but 2000s movies lack that high concept absurdity that could make “Face/Off” a classic. It doesn’t matter if the dialogue is atrocious, if the pseudo-science doesn’t make a lick of sense or if the surrounding characters are so thick as to possibly think this plan, of surgically giving Archer Troy’s face so that he can infiltrate a prison and get information out of Troy’s brother, is a good idea.

The concept alone is juicy, but Nic Cage being in the role consequently enhances Travolta’s performance, who starts to channel Cage’s mannerisms, his slick and sleazy attitude and villainous posture. Cage doesn’t precisely act like Travolta, but you recognize that the two of them are both giving performances within performances, and you’d be forgiven for confusing the two, thinking Cage somehow inhabits Travolta and was playing the real Castor Troy all along.

Smaller details emphasize the breadth of Woo’s mastery over the form. Inside the prison, where all the guards are one-dimensional monsters, the prisoners wear magnetic boots that lock them to the floor and track their movements, a detail so silly and outrageous that you remember it even though it has no bearing on the story.

Although you could see why Woo’s style would eventually go out of fashion. When a movie is this populated with people diving through glass windows away from explosions in slow motion at domineering low angles, it can get a little old. It’s when he pitches these set pieces at such a high degree of insanity, like the biggest Mexican standoff at the film’s climax, or when “Over the Rainbow” plays over a bullet-ridden bloodbath that would lay the groundwork for “The Matrix.” And don’t forget the doves!

The style and tone that “Face/Off” portrays has become nothing but cliches and has aged poorly, but the film itself hasn’t aged a day. It’s as fresh, exciting and fun as it was in 1997.

The thing about Bill Murray movies is, they often don’t work without him. “Groundhog Day” would be a horrible Adam Sandler comedy if anyone but him played the part, and the same is true of “Ghostbusters.” Aside from all the ugly misogyny that’s being thrown at the movie sight unseen, no wonder everyone is freaking out over a remake of “Ghostbusters.”

The thing about Bill Murray movies is, they often don’t work without him. “Groundhog Day” would be a horrible Adam Sandler comedy if anyone but him played the part, and the same is true of “Ghostbusters.” Aside from all the ugly misogyny that’s being thrown at the movie sight unseen, no wonder everyone is freaking out over a remake of “Ghostbusters.”

Does Pixar have a sequel problem? I doubt it. We can debate the quality of “Cars 2” and “Monsters University,” but “Finding Dory” succeeds because it takes one of the more iconic and unique characters within the Pixar canon and gives her meaningful depth and a story of her own. To me, that’s not Pixar trying to cash in on a few more toys.

Does Pixar have a sequel problem? I doubt it. We can debate the quality of “Cars 2” and “Monsters University,” but “Finding Dory” succeeds because it takes one of the more iconic and unique characters within the Pixar canon and gives her meaningful depth and a story of her own. To me, that’s not Pixar trying to cash in on a few more toys.

If you’re feeling down, if everything seems to be at its lowest, don’t worry. Life isn’t so bad. After all, we have farts! Farts are magical. They spray from our butts, they smell and make a funny sound. How wonderful is that? Why don’t we recognize this every day of our lives and use farts to discover all the other amazing things human beings are capable of. Shout to the heavens! We have farts!

If you’re feeling down, if everything seems to be at its lowest, don’t worry. Life isn’t so bad. After all, we have farts! Farts are magical. They spray from our butts, they smell and make a funny sound. How wonderful is that? Why don’t we recognize this every day of our lives and use farts to discover all the other amazing things human beings are capable of. Shout to the heavens! We have farts!

The films of Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda all border on schmaltz and insignificance. But his deft hand and simple storytelling consistently reveal deep truths about life and family with delicate nuance. His latest film, “Our Little Sister,” offers the same tender spirit and warm glow with a perceptive look at the ups and downs that face the modern young woman.

The films of Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda all border on schmaltz and insignificance. But his deft hand and simple storytelling consistently reveal deep truths about life and family with delicate nuance. His latest film, “Our Little Sister,” offers the same tender spirit and warm glow with a perceptive look at the ups and downs that face the modern young woman.

If Barbara Kopple were making “Harlan County U.S.A.” today it would be focused on environmental ramifications of coal mining and the broader corruption of big business and Wall Street over the little guy, and only then would it look at the health and safety conditions provided to the common working man. And yet it’s remarkable how relevant Kopple’s pinnacle documentary, 40 years after its initial release, still feels today.

If Barbara Kopple were making “Harlan County U.S.A.” today it would be focused on environmental ramifications of coal mining and the broader corruption of big business and Wall Street over the little guy, and only then would it look at the health and safety conditions provided to the common working man. And yet it’s remarkable how relevant Kopple’s pinnacle documentary, 40 years after its initial release, still feels today. Always get the name of the dog. That’s a reporting tip to find that extra detail that your audience will remember. In Todd Solondz’s latest film “Wiener-Dog,” this little brown dachshund goes from being named Doody to Cancer between four separate owners, and each name seems to reflect something different about the quirky, strange people behind it.

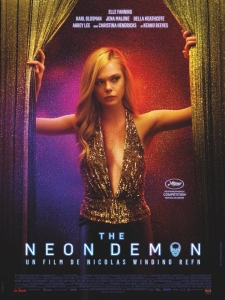

Always get the name of the dog. That’s a reporting tip to find that extra detail that your audience will remember. In Todd Solondz’s latest film “Wiener-Dog,” this little brown dachshund goes from being named Doody to Cancer between four separate owners, and each name seems to reflect something different about the quirky, strange people behind it. “Am I staring?” In these first few lines of “The Neon Demon,” Director Nicolas Winding Refn’s invitation to stare gives his latest film both its perverse pleasure and questionable subtext. With “Drive” and “Only God Forgives,” Refn’s films have long been a combination of the violent and tantalizing. So it’s natural that the Danish director would make “The Neon Demon,” a psycho-horror art house drama about beauty and the grotesque pursuit of perfection. And while it works as stunning exploitation cinema, it’s perhaps less so as a comment on the fashion world it’s depicting.

“Am I staring?” In these first few lines of “The Neon Demon,” Director Nicolas Winding Refn’s invitation to stare gives his latest film both its perverse pleasure and questionable subtext. With “Drive” and “Only God Forgives,” Refn’s films have long been a combination of the violent and tantalizing. So it’s natural that the Danish director would make “The Neon Demon,” a psycho-horror art house drama about beauty and the grotesque pursuit of perfection. And while it works as stunning exploitation cinema, it’s perhaps less so as a comment on the fashion world it’s depicting. Nostalgia does strange things to people. “WarGames” was a major blockbuster in 1983, the fifth highest grossing movie of the year and even the recipient of three Oscar nominations. I watched it because the film has a prominent place in the book “Ready Player One,” in which the lead character Parzival steps into David Lightman’s shoes and gets to act out the entire movie virtually. And yet it’s strange to think that anyone, even Ernest Cline, would imagine the film has aged well.

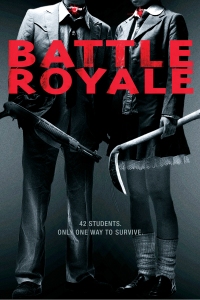

Nostalgia does strange things to people. “WarGames” was a major blockbuster in 1983, the fifth highest grossing movie of the year and even the recipient of three Oscar nominations. I watched it because the film has a prominent place in the book “Ready Player One,” in which the lead character Parzival steps into David Lightman’s shoes and gets to act out the entire movie virtually. And yet it’s strange to think that anyone, even Ernest Cline, would imagine the film has aged well. It’d be impossible not to compare “Battle Royale” with “The Hunger Games.” Conceptually, they’re identical. A tyrannical government has instated a law in which teenagers are forced to compete in a fight to the death in order to win their freedom.

It’d be impossible not to compare “Battle Royale” with “The Hunger Games.” Conceptually, they’re identical. A tyrannical government has instated a law in which teenagers are forced to compete in a fight to the death in order to win their freedom.