I loved Harry Potter. I read all the books as a kid multiple times through, although what kid in the early 2000s didn’t? I remember waiting in line at Target late at night to get my copy as soon as the new book became available. On long vacations, my sister and I would take turns reading a chapter at a time. For Halloween, I dressed as Harry in a custom cloak sewed by my grandmother. My friend went trick or treating with me as Ron Weasley. Sitting in the multiplex seats on opening night before one of the films, I named the four creators of the Marauder’s Map (Moody, Wormtail, Padfoot and Prongs) and won myself a movie poster. And when “The Prisoner of Azkaban” came out, I got a gigantic crush on Emma Watson (it hasn’t gone away).

But when I got to college, things changed. I did a story for the student newspaper about people who played in Quidditch clubs and made their own wands. Of all the sights to see in London, friends of mine went out of their way to take photos at Platform 9 & ¾. I started blocking and ignoring friends on Facebook because they constantly shared Buzzfeed articles and quizzes about what houses they belonged to, how hot Neville Longbottom has gotten, and what the entire friggin’ movie series would look like from Hermione’s point of view.

What happened? My love didn’t lessen over the years. But I clearly didn’t have this same obsession that so many others did. I was not like these people. I was not a Potterhead.

Here’s another one. I had shelves full of Legos as a kid, massive displays that I spent hours slaving over, playing with and imagining stories. But then there were the kids who created fantastic works of art with Legos that never matched the box. They attended conventions where they could practice and experiment with Lego’s robotics, spawning innovation for years to come. This wasn’t me either.

My obsession with Pokémon probably surpassed them all. I had two giant binders filled with Pokémon cards that dwarfed any collections of my friends. I’d be terrified to count just how much money my family spent on cards over the years. I loved playing the trading card game, even if my friends found it tedious. I watched the TV show religiously and poured hours into all the GameBoy games. Ash Ketchum was yet another Halloween costume of mine.

But what about the kids who competed in massive tournaments and conventions exclusively for real Pokémon masters? I never took my fandom with Pokémon beyond the backyard, but I could’ve been online at a young age, finding people all over the world who loved the game as much as I did. That didn’t happen.

The easy observation is that there will almost always be people more passionate than you about something, someone who is crazier, has gone to longer lengths, spent more money, time and effort. It’s very hard to be the absolute best at anything, be it sports, music or total fandom.

But in the 21st Century, we define ourselves not by how we dress or the games we play, but the things we share online, the arbitrary status symbols and activities that show we stand apart. If you didn’t tweet it, tag it, snap it or Instagram it, it may as well not have happened. And you must not really be a fan unless you’re on the right message boards, have the right followers on Twitter and have crafted an online presence to show how much you care.

All my life I’ve loved many things and devoted myself passionately to many hobbies, but only recently have I come to realize that I never directly aligned myself with any of these groups, subcultures, or whatever you wish to call them in 2016. I’m a film critic. That’s what I “do” but is it “my thing?”

It gets more difficult as I apply to jobs and have to work on defining my “brand” to prospective employers. Someone asked me during a job interview if I was into “nerd culture,” and I had to stumble for an answer. Sure, I know a lot about the Marvel movies, have seen most of them, am aware of some of the Easter eggs and nuances because I need to be in order to do my job. In the case of “Star Wars,” I even love it, but I’d be lying if I said I was the person most capable and interested in writing about it. That’s not my “thing.” I had to say I was a nerd for other things, like Wes Anderson and Tilda Swinton. If only fandom for those things paid the bills.

But even within film criticism, I’d be hard pressed to say I’ve carved out a niche. When people ask me what kind of movies I like, I tend to give a snarky answer and say, “I like movies that are good.” When I say that, it means I don’t have a preference for a genre, an era or a style. If a movie is well made and is interesting, I’m interested. It doesn’t even have to be “good.”

But at the same time, there are some people know the horror genre up and down, having gobbled up every junky, schlocky B-movie to come out of Fantastic Fest. Some people have watched every Bette Davis movie and have a poster of Robert Osborne up in their bedrooms (maybe).

Should I go to the trouble of sitting through every silent film I can get my hands on so that I can call myself an expert in a specific genre or medium? There’s animation, foreign films, documentaries, musicals, digital web based films, art installations, you name it. Will mastering any one of these things make me a better critic? Or more likely to get a job? Or happier? Or will I still fall into the trap of being second best?

And honestly, who has the time? I write about most movies I see, but I watch them because I want to. If I go on a Jim Jarmusch binge it’s because I’m in the mood, not because I consciously assigned myself that work. Maybe that should change.

I’ve also always learned throughout journalism school that the way to get a job is to be versatile. That means being able to write as well as do video, photos, radio, social media, etc. But it’s also meant to me that I should absorb the world broadly. I watch films of all stripes, I watch TV and listen to a ton of music. I read about politics, sports, science and even sometimes am curious about things like cooking or fashion. I tend to feel that if a movie is good enough, if an article is well written, I can get interested in anything.

I’ve been asking a lot of questions here, and I don’t necessarily mean them rhetorically. What can I do to be a better critic, scholar, fan, and even a friend?

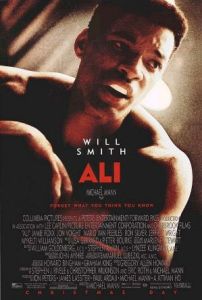

I learned a lot about Muhammad Ali in the wake of his death a few weeks back. His fighting record was stellar, and there are so many wonderful photos of Ali with other geniuses who all saw him as The Greatest, but he’s the most important sportsman of all time because he changed the game and changed the world.

I learned a lot about Muhammad Ali in the wake of his death a few weeks back. His fighting record was stellar, and there are so many wonderful photos of Ali with other geniuses who all saw him as The Greatest, but he’s the most important sportsman of all time because he changed the game and changed the world. A lot of generic biopics about geniuses get a pass because they show an endearing side to a beloved figure. I can swallow a mediocre movie about “The Doors” because Val Kilmer is so electric as Jim Morrison on stage and I love the music.

A lot of generic biopics about geniuses get a pass because they show an endearing side to a beloved figure. I can swallow a mediocre movie about “The Doors” because Val Kilmer is so electric as Jim Morrison on stage and I love the music. Across the “Lethal Weapon” movies and “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang,” few directors have been as consistently successful with action comedies as Shane Black. In his latest film “The Nice Guys,” he’s combined that penchant for irreverence and slick action into a hilarious, scandalous, seedy noir in the vein of “L.A. Confidential” and a Judd Apatow bromance.

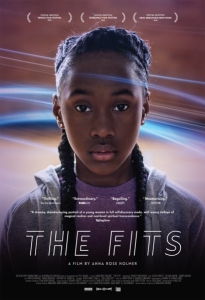

Across the “Lethal Weapon” movies and “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang,” few directors have been as consistently successful with action comedies as Shane Black. In his latest film “The Nice Guys,” he’s combined that penchant for irreverence and slick action into a hilarious, scandalous, seedy noir in the vein of “L.A. Confidential” and a Judd Apatow bromance. Working out is overrated, and so is “The Fits,” a new indie film by first time director Anna Rose Holmer. The adrenaline and endorphin rush you get from exercise and activity has been visualized in punishing, stimulating style in war films, boxing films, you name it. But these films channel the sensation of putting yourself through that pain alongside other emotional conflict.

Working out is overrated, and so is “The Fits,” a new indie film by first time director Anna Rose Holmer. The adrenaline and endorphin rush you get from exercise and activity has been visualized in punishing, stimulating style in war films, boxing films, you name it. But these films channel the sensation of putting yourself through that pain alongside other emotional conflict. If you could be transformed into any animal, which would it be? It sounds like a bad question on a dating website, and yet we’ve become more reliant on such quirks in defining relationships and romance. Colin Farrell chooses to be the title animal in “The Lobster,” an absurdist satire that uses a hilariously bizarre, futuristic premise to lampoon the idea of modern love.

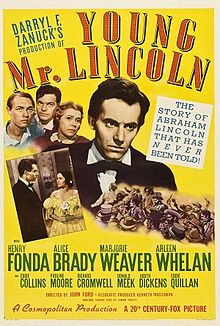

If you could be transformed into any animal, which would it be? It sounds like a bad question on a dating website, and yet we’ve become more reliant on such quirks in defining relationships and romance. Colin Farrell chooses to be the title animal in “The Lobster,” an absurdist satire that uses a hilariously bizarre, futuristic premise to lampoon the idea of modern love. “You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.”

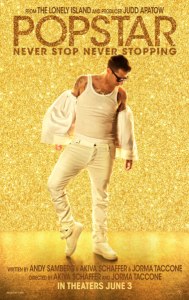

“You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.”  If you’re going to make a joke song, at least make it a good song. That was the sentiment the Coen Brothers had when writing “Please Mr. Kennedy,” and if The Lonely Island were around in 1960s Greenwich Village, they might’ve recorded just that. As far as fake joke bands go, no one gets more studio star power and indelible hooks to go along with their ridiculous lyrics about jizzing in pants or dicks in boxes. They do hilarious comedy but also make great music.

If you’re going to make a joke song, at least make it a good song. That was the sentiment the Coen Brothers had when writing “Please Mr. Kennedy,” and if The Lonely Island were around in 1960s Greenwich Village, they might’ve recorded just that. As far as fake joke bands go, no one gets more studio star power and indelible hooks to go along with their ridiculous lyrics about jizzing in pants or dicks in boxes. They do hilarious comedy but also make great music.

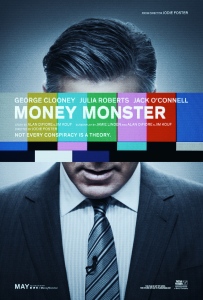

She’s as mad as hell and she isn’t going to take it anymore. Jodie Foster’s “Money Monster” (her follow-up to “

She’s as mad as hell and she isn’t going to take it anymore. Jodie Foster’s “Money Monster” (her follow-up to “