You could be forgiven for calling “Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising” the most feminist movie of the year. Such is the state of Hollywood movies when there are so few truly female-fronted blockbusters and comedies that a movie in which teenage girls chuck their bloody tampons into Seth Rogen’s mouth could be considered progressive. But whether or not Rogen and company have made a feminist raunch-fest, they’ve made an often hilarious sequel that at least begs the question.

You could be forgiven for calling “Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising” the most feminist movie of the year. Such is the state of Hollywood movies when there are so few truly female-fronted blockbusters and comedies that a movie in which teenage girls chuck their bloody tampons into Seth Rogen’s mouth could be considered progressive. But whether or not Rogen and company have made a feminist raunch-fest, they’ve made an often hilarious sequel that at least begs the question.

“I don’t even know what’s sexist,” Rogen’s character says in desperation at one point in “Neighbors 2.” Director Nicholas Stoller could be breaking boundaries or crossing serious lines, but at the end of the day he’s trying to make a funny movie. The divide between sharp political satire and what could be considered offensive and insensitive is often blurry.

Here’s the ugly truth that “Neighbors 2” brings to light: sororities on American campuses are not allowed to throw parties, but frats can. Stoller perfectly captures modern Greek life in a quick early scene, with Selena Gomez leading a flock of girls all dressed in white while wearing halos made of flowers. Their delicate golf claps say it all. Shelby, Beth and Nora (Chloe Graec Moretz, Kiersey Clemons, Beanie Feldstein) together reject this culture and decide that instead of rushing a sorority where they can’t smoke weed and where frat houses literally have “giant arrows pointing upstairs to fuck us,” they’ll start their own sorority, right next door to Mac and Kelly Radner (Rogen and Rose Byrne).

Time and again the movie reminds us that if a man were doing the crazy, vulgar, potty and drug humor that happens here, no one would bat an eye. To be fair, “Neighbors 2” may be pushing its luck; “Bridesmaids” never had to tell the audience how forward thinking it was to have women acting filthy. But Stoller is smart enough to wink at the audience in that, like in the original “Neighbors,” both the Radners and the college kids next door are man-sized children not nearly as mature as they pretend to be.

“Neighbors” was a riot because it flipped the script of what a crazy frat bro could look like in creative ways, and the sequel has more of the same. Zac Efron returns to continue spending the bulk of his time shirtless, even briefly turning into Magic Mike, but at the same time he and his brothers will pull out a ukulele and sing Jason Mraz during a gay wedding proposal. This movie could arguably be as queer as it is feminist.

What’s new has all to do with the girls. They dress like Minions as a form of hazing. They watch “The Fault in Our Stars” all together in their pajamas. They dress up like feminist icons Oprah and First Lady Hillary Clinton, Senator Hillary Clinton, and future President Hillary Clinton. Five dudes may have written the screenplay, but it feels like comedy for women, not just gross-out comedy performed by women.

“Neighbors 2” doesn’t gel quite as well as the original, but it has equal doses of Rogen and Byrne’s dopey chemistry, not to mention some impressively funny cinematic style. Stoller can stage a pretty solid pratfall, and there’s one hilarious sequence where Rogen and Efron, each shirtless and jiggling, are running through a hazy orange fog as “Sabotage” plays in the background. It would be funny even if they weren’t being chased by teenage girls trying to steal back their trash bag full of weed.

So whether “Neighbors 2” is feminist is beside the point. Stoller’s having a lot of fun, and the girls will too.

3 ½ stars

John Carney’s “Sing Street” is a marvelous throwback to a time when kids defined their personality and their fashion by the music they loved, when music videos first showed us what cool looked like, and when a dream of being famous meant picking up a guitar and joining a band. Music has the power to shape the person we become, and the music and culture of “Sing Street” have imbued this coming of age story with so much life, energy and spirit.

John Carney’s “Sing Street” is a marvelous throwback to a time when kids defined their personality and their fashion by the music they loved, when music videos first showed us what cool looked like, and when a dream of being famous meant picking up a guitar and joining a band. Music has the power to shape the person we become, and the music and culture of “Sing Street” have imbued this coming of age story with so much life, energy and spirit. “Ooh, a conspiracy,” says one of the members of the trapped and tortured punk band in “Green Room.” These kids are so punk that even when they’re being slaughtered one by one, they still have room for sarcasm. But it’s not a conspiracy, “just a clusterfuck.”

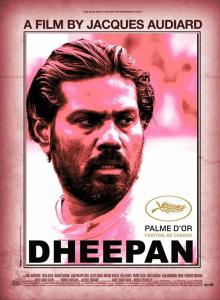

“Ooh, a conspiracy,” says one of the members of the trapped and tortured punk band in “Green Room.” These kids are so punk that even when they’re being slaughtered one by one, they still have room for sarcasm. But it’s not a conspiracy, “just a clusterfuck.” In “Dheepan,” a Sri Lankan Tamil warrior gets smuggled into France as a refugee, but not before being paired with a family who will allow him to escape. A 25-year-old woman searches the Sri Lankan slums and plucks an orphan 9-year-old girl from the crowd to pose as her daughter. In an instant, the three are in this together.

In “Dheepan,” a Sri Lankan Tamil warrior gets smuggled into France as a refugee, but not before being paired with a family who will allow him to escape. A 25-year-old woman searches the Sri Lankan slums and plucks an orphan 9-year-old girl from the crowd to pose as her daughter. In an instant, the three are in this together. Marvel’s head-honchos must’ve spent years dreaming up this moment. It’s the moment when Captain America, Iron Man and 10 other superheroes all dash at one another in anticipation of an epic death match. This battle is why we’ve sat through these movies since 2008, and it’s everything fans could’ve asked for.

Marvel’s head-honchos must’ve spent years dreaming up this moment. It’s the moment when Captain America, Iron Man and 10 other superheroes all dash at one another in anticipation of an epic death match. This battle is why we’ve sat through these movies since 2008, and it’s everything fans could’ve asked for. Near the beginning of “Tale of Tales” a slender, cloaked old man slinks his way into the palace of the King and Queen of Longtrellis (John C. Reilly and Salma Hayek) to bestow upon them a prophecy. The Queen is desperate to have a child, and she agrees to the specter’s challenge: “Hunt a sea monster, cut out its heart, have the heart cooked by a virgin, she must be alone, then eat the heart, and you will become pregnant.”

Near the beginning of “Tale of Tales” a slender, cloaked old man slinks his way into the palace of the King and Queen of Longtrellis (John C. Reilly and Salma Hayek) to bestow upon them a prophecy. The Queen is desperate to have a child, and she agrees to the specter’s challenge: “Hunt a sea monster, cut out its heart, have the heart cooked by a virgin, she must be alone, then eat the heart, and you will become pregnant.” Between the mud wrestling, the promiscuous sex, the time spent driving around on the hunt for tail, playing ping pong and talking endlessly about baseball, there’s more than a little wish fulfillment going on in “Everybody Wants Some!!” Richard Linklater’s latest is actually more personal to him than his previous film “

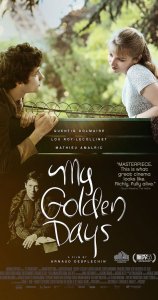

Between the mud wrestling, the promiscuous sex, the time spent driving around on the hunt for tail, playing ping pong and talking endlessly about baseball, there’s more than a little wish fulfillment going on in “Everybody Wants Some!!” Richard Linklater’s latest is actually more personal to him than his previous film “ The ability to compare your girlfriend to an Italian work of landscape art from the Renaissance, to carry out a long distance relationship of casual sex, or to have an affair with your housemate’s girlfriend without consequence, is all decidedly French. Arnaud Desplechin’s “My Golden Days” follows a romance and coming-of-age story very specific to a Parisian lifestyle in the ‘80s, so frivolous and carefree that watching it feels erratic.

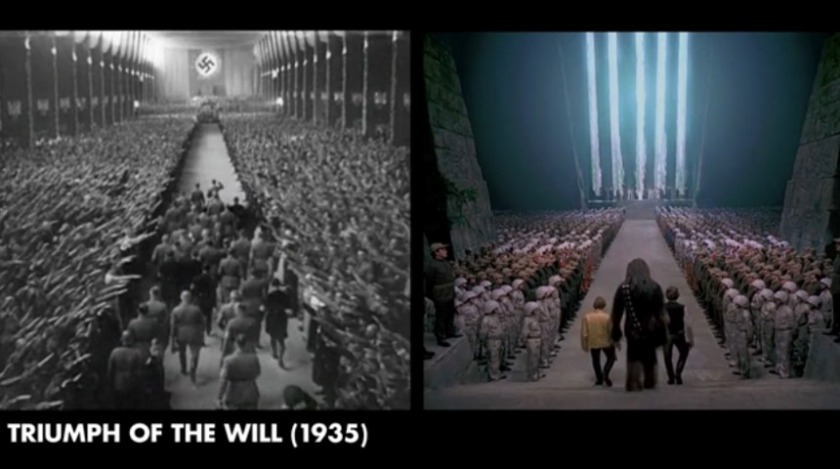

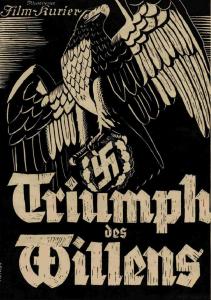

The ability to compare your girlfriend to an Italian work of landscape art from the Renaissance, to carry out a long distance relationship of casual sex, or to have an affair with your housemate’s girlfriend without consequence, is all decidedly French. Arnaud Desplechin’s “My Golden Days” follows a romance and coming-of-age story very specific to a Parisian lifestyle in the ‘80s, so frivolous and carefree that watching it feels erratic. Editor’s Note: This piece was written for a class in which we were instructed to review a film that is considered controversial, acknowledging how it can still be viewed as a work of art despite its controversy.

Editor’s Note: This piece was written for a class in which we were instructed to review a film that is considered controversial, acknowledging how it can still be viewed as a work of art despite its controversy.