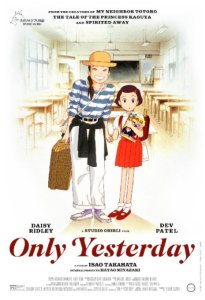

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

For her vacation from work in the city, 27-year-old Taeko decides to visit her family in the countryside to work on their farm. As she travels, she reflects back on her life as a child. The 10-year-old Taeko (Youko Honna) is spunky, sunny and just a little bashful and spoiled. She’s a typical little girl, so overwhelmed with joy as she visits a bath house that she faints, mystified by how to cut open a pineapple, and so smitten and petrified in her crush on the cute, 5th Grade pitcher of the baseball team.

“Only Yesterday” shares the look of all Studio Ghibli animated films, with soft pastel colors and rich, painterly, hand drawn detail within every frame. But unlike the fantastical tropes of Hayao Miyazaki’s many films within the studio, Takahata grounds “Only Yesterday” in reality. The film’s modest scale only make the many slices of life more beautiful.

Takahata made the film back in 1991 (since then he’s been nominated for an Oscar with “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya” in 2013), but Disney originally blocked its American release due to a scene in which the naïve kids start piecing together what it means to have a period. Sure enough, “Only Yesterday” approaches many mature, adult themes through young eyes. Similarly, Takahata’s masterpiece “Grave of the Fireflies,” his previous film in 1988, deals with war, violence and death in a way that perhaps a child can understand.

“Only Yesterday” however finds tragedy in smaller moments. In one scene, Taeko gets a single line in a play, and though she’s discouraged from improvising new lines, she makes the most of it in her performance and gets offered a part in a college production. Her fantasy about fame blooms to life in preciously hilarious pinks, yellows and greens around her. It’s adorable, and it’s so intimate that it hurts all the more when her father quietly puts his foot down and dashes her dreams. In another, Taeko gets a D on a math test because she doesn’t understand dividing fractions. She draws a picture of an apple and cuts it into pieces, so she’s clearly practical, but her older sister thinks there must be something wrong with her, and it’s devastating to see Taeko within earshot of her sister’s ridiculing.

Of course the spirit of any Studio Ghibli movie lies in its animation. Every film that has ever come from this studio has a meticulous, loving care in each still frame. Takahata literally blurs the frame itself to give “Only Yesterday” a hint of magic. After a baseball game, Taeko quickly runs home to avoid the boy she has a crush on. Though he’s just as bashful, the boy chases after her, and there he is, standing in the distance, a small figure at the end of an alley. The bright orange sunset is just behind him, and everything else in the frame is white and washed of its color, with the edges of the foreground specifically erased to create a sense of depth within the 2D, animated frame. He mumbles out a question: “Do you like sunny, rainy, or cloudy days?” She stutters out her answer, “c-c-cloudy,” they both smile, and he runs off. Taeko then turns down the block and starts to seemingly climb up the frame and fly away. You’ll melt watching it.

“Only Yesterday” drips with warm, fuzzy sensations of nostalgia. The childhood story and characters are whimsical and light-hearted but are concerned with intimate, personal truths about life in a way that would be meaningful at any age.

4 stars

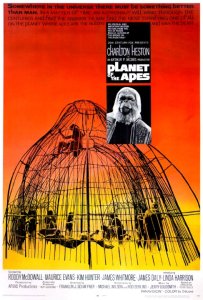

Watching “Planet of the Apes” today is like trying to sway a climate change denier or a Creationist: it’s not going anywhere and after a while it gets pretty tiring.

Watching “Planet of the Apes” today is like trying to sway a climate change denier or a Creationist: it’s not going anywhere and after a while it gets pretty tiring. “Embrace of the Serpent” mysteriously and surreally takes us on a journey through nature and history to examine the value of preserving culture in the face of radical, profound change. Told in two time periods surrounding the Amazonian shaman Karamakate’s encounters both as a young and old man with visiting white men, Ciro Guerra’s Oscar nominated foreign language film finds unexplored twists in the culture clash narrative and delivers an entrancing look at the jungle through a native’s eye.

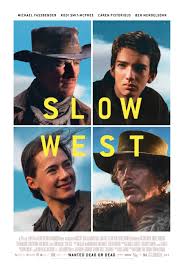

“Embrace of the Serpent” mysteriously and surreally takes us on a journey through nature and history to examine the value of preserving culture in the face of radical, profound change. Told in two time periods surrounding the Amazonian shaman Karamakate’s encounters both as a young and old man with visiting white men, Ciro Guerra’s Oscar nominated foreign language film finds unexplored twists in the culture clash narrative and delivers an entrancing look at the jungle through a native’s eye. Lying on the ground in the Old West, a naïve boy and a grizzled bounty hunter look up to the moon and constellations in the night sky. The boy cocks his fingers into a gun and shoots holes in the heavens, and the bounty hunter says that when we finally get to the moon, the first thing we’re likely to do is kill all the natives that live there. Even space is a reflection of their bleak reality.

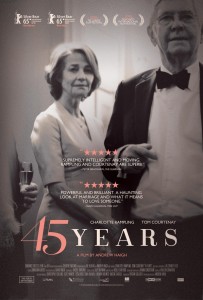

Lying on the ground in the Old West, a naïve boy and a grizzled bounty hunter look up to the moon and constellations in the night sky. The boy cocks his fingers into a gun and shoots holes in the heavens, and the bounty hunter says that when we finally get to the moon, the first thing we’re likely to do is kill all the natives that live there. Even space is a reflection of their bleak reality. “They found her body…I know I told you about my Katia.” That little word “my” effectively seals the fate of the marriage of Kate and Geoff Mercer in Andrew Haigh’s film “45 Years.”

“They found her body…I know I told you about my Katia.” That little word “my” effectively seals the fate of the marriage of Kate and Geoff Mercer in Andrew Haigh’s film “45 Years.” In “The Witch,” the latest in a hot streak of indie horror films, the devil is only half of this family’s problems.

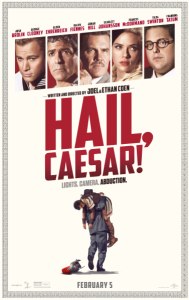

In “The Witch,” the latest in a hot streak of indie horror films, the devil is only half of this family’s problems. The Coen brothers’ “Hail, Caesar!” acts as a sizzle reel for all the classic Hollywood film genres the pair could’ve honored and lampooned throughout their career but never got the chance. It shows how the Coens might do a sword and sandal epic, a lush costume melodrama or even a Gene Kelly musical. But “Hail, Caesar!” is a movie about the future, a post-modern mish-mash of genres and styles that hints at where history will take cinema as much as it is a throwback. The Coens are having a lot of goofy fun but still manage a surreal, captivating art picture on par with many of their classics.

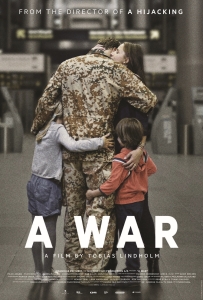

The Coen brothers’ “Hail, Caesar!” acts as a sizzle reel for all the classic Hollywood film genres the pair could’ve honored and lampooned throughout their career but never got the chance. It shows how the Coens might do a sword and sandal epic, a lush costume melodrama or even a Gene Kelly musical. But “Hail, Caesar!” is a movie about the future, a post-modern mish-mash of genres and styles that hints at where history will take cinema as much as it is a throwback. The Coens are having a lot of goofy fun but still manage a surreal, captivating art picture on par with many of their classics. “A War,” the Danish film nominated for this year’s Best Foreign Language Oscar, is the rare war film to consider a soldier’s practical war as well as a moral one. It’s not just about coping with life after war, but about how a soldier faces hard decisions and consequences upon returning home.

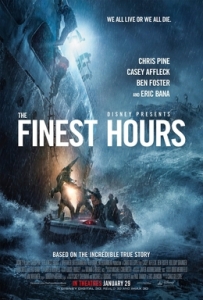

“A War,” the Danish film nominated for this year’s Best Foreign Language Oscar, is the rare war film to consider a soldier’s practical war as well as a moral one. It’s not just about coping with life after war, but about how a soldier faces hard decisions and consequences upon returning home. The members of the Coast Guard don’t get the credit that cops, firefighters or soldiers do for saving lives. “The Finest Hours,” Disney’s telling of an historic rescue mission, is full of heroics but also people just doing their job. It’s a sentimental, old-fashioned thriller but is also endearingly modest.

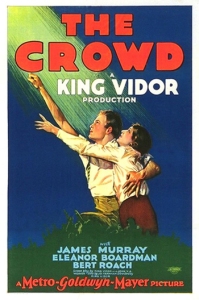

The members of the Coast Guard don’t get the credit that cops, firefighters or soldiers do for saving lives. “The Finest Hours,” Disney’s telling of an historic rescue mission, is full of heroics but also people just doing their job. It’s a sentimental, old-fashioned thriller but is also endearingly modest. Has any single image in film history better captured the idea of conformity and order than the endless rows of identical desks in a vast office building in King Vidor’s “The Crowd”? Shot on a slant and tracked overhead to infinity, it’s one moment of many that display 1920s New York City as a futuristic, even surreal cityscape representative of all the world’s uniformity and ceaseless rat race. Vidor films at towering low angles that give New York such gravitas and immense presence, from skyscrapers that look like temples and the glistening lights of Coney Island that look heavenly.

Has any single image in film history better captured the idea of conformity and order than the endless rows of identical desks in a vast office building in King Vidor’s “The Crowd”? Shot on a slant and tracked overhead to infinity, it’s one moment of many that display 1920s New York City as a futuristic, even surreal cityscape representative of all the world’s uniformity and ceaseless rat race. Vidor films at towering low angles that give New York such gravitas and immense presence, from skyscrapers that look like temples and the glistening lights of Coney Island that look heavenly.