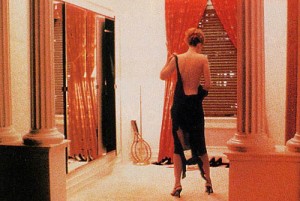

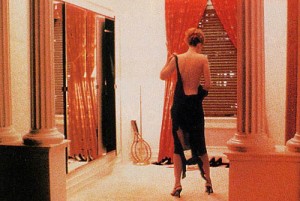

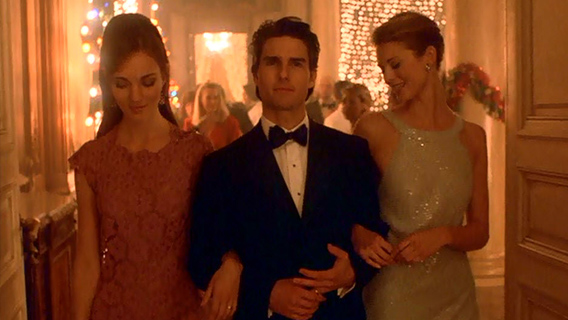

The opening shots of Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut” are a tease. Nicole Kidman strips off her slinky black dress in a quick moment of voyeurism and sexuality. A strangely lilting waltz plays over the top, and Kubrick drops us not into a boudoir or a ravishing sex scene but the mundane act of a married couple getting ready for a night out. But the real tease comes in its opening sequence amid something of a slice of heaven. The opulent party at the home of Victor Zeigler (Sydney Pollack) is bathed in blinding white light and a soothing haze lingers over the whole room. Kubrick catches the moment with a lingering focus, slowly observing and backtracking his camera into the gleam.

The opening shots of Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut” are a tease. Nicole Kidman strips off her slinky black dress in a quick moment of voyeurism and sexuality. A strangely lilting waltz plays over the top, and Kubrick drops us not into a boudoir or a ravishing sex scene but the mundane act of a married couple getting ready for a night out. But the real tease comes in its opening sequence amid something of a slice of heaven. The opulent party at the home of Victor Zeigler (Sydney Pollack) is bathed in blinding white light and a soothing haze lingers over the whole room. Kubrick catches the moment with a lingering focus, slowly observing and backtracking his camera into the gleam.

Kubrick’s “Lolita” opens with two teases of its own. The first is an iconic one a good 20 minutes deep, in which Prof. Humbert Humbert (James Mason) gets his first look at the underage vixen that is Lolita (Sue Lyon), perched languidly in a sun bathing hat, sunglasses and a frilly bikini. The shot is as deceptively alluring as Kidman’s. But the real tease is the opening sequence in which Humbert enters into the sprawling mansion of Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers), the site of a long deserted orgy. Quilty’s cluttered home of paintings, pianos and ping pong tables looks like it could belong to Charles Foster Kane. He even drops a quick line about being Spartacus, this being the movie Kubrick made following his ancient war epic. But the hint of glamour and sense of building tension seen here does not begin to set the tone for the remainder of “Lolita”.

“Eyes Wide Shut” and “Lolita” are the two most sexual films in Kubrick’s filmography. There’s no sexuality in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, or in “The Shining”. There’s plenty of nudity in “A Clockwork Orange” but none of the “‘ole in and out” is really about sex. And any sexual tension found in “Spartacus” may be purely accidental.

What’s remarkable is how uninterested he is in sexuality in both “Eyes Wide Shut” and “Lolita”, how he uses the tantalizing possibilities as a diversion. “Eyes Wide Shut” was billed as a steamy sex romance between Hollywood’s then biggest power couple, but Kubrick uses orgies, prostitution, and bedroom pillow talk to stage an elaborate metaphor about fidelity. Similarly, “Lolita” was billed as the movie that simply could not have been made, one so scandalous in its subject matter, that how could it ever pass censors? And yet the film is often a farce, focused on the mundane and the ordinary slices of marriage and suburbia over the scandal.

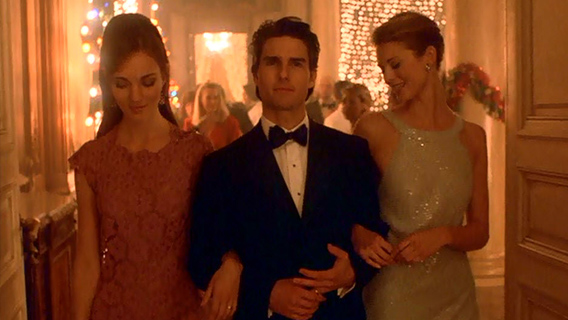

Kubrick may be most interested in how dangerous sexuality can be. The first truly provocative sexual scene in “Eyes Wide Shut” involves Tom Cruise as Dr. Bill Harford tending to Zeigler in one of his many “house calls”. A ravishing model type is completely nude and passed out in a chair after having done too many drugs. But the scene is tame. Cruise plays everything so cool and professional, calm and reassuring that he saps the moment of its sexuality.

As for Humbert Humbert, he so quickly allows sexual desire for Lolita to warp his mind, to the point that he’s punished for even entertaining such thoughts. He’s now married to the shrill, needy and pitiful Charlotte (Shelley Winters), only to realize that Charlotte has no intention of bringing Lolita back into their lives. The whole point of this sham marriage was to remain close to Lolita, and when that’s in jeopardy he begins conceiving “the perfect murder”. Just that stray thought causes him to drop his guard, allowing Charlotte to find his diary and secret affections for her daughter.

There’s a spiritual sensation to sex in each of Kubrick’s films as well. “Eyes Wide Shut” is very clearly something of an existential journey. Cruise’s Bill is an affluent figure dragged through set pieces that are luxurious, grounded, dreamy, seedy, erotic, and plain bizarre. Each seems detached from the other, and Kubrick has erased a strong sense of time that would unify them. What’s more, we’re kept in the dark as much as Bill is. His keyboard playing friend hints to him about some of the most beautiful women he’s ever laid eyes on, but as he walks into that ancient, foreboding mansion, Kubrick doesn’t tease us as to what to really expect there. We’re going in dark, and when the pagan ritual and orgy does arrive, we’re made into spectators. Only a handful of films manage this much nudity and sex and feel completely sterile.

That aspect of course was what turned off so many critics to “Eyes Wide Shut” upon its release. It’s a movie with no heat, one wrote, but then Kubrick was always polarizing. Everything about the movie is a diversion away from sex, and given Bill’s many opportunities and temptations, he never succumbs. The orgy and everything in between is a stigma for his own fears and insecurities about his wife and marriage. The heat then is in the tension and conspiracy, how temptations may come back to punish Bill.

Humbert’s journey is less spiritual, but still profound. Kubrick uses Lolita and Quilty to toy with him, to drive him to madness. Humbert starts by dancing around the news of Charlotte’s death and how to best approach Lolita, but she can play coy and read him like a book. Her dialogue, all carefully within Production Code standards, toes the line between daughterly affection and something more lewd. Once they’ve relocated to Ohio, their affair gets a little less subtle, and even the neighbors begin to pick up on it. Soon Humbert’s hapless etiquette and politeness make him look tone deaf and alien. He’s overprotective and hyper attentive to Lolita in exactly the way she demands, but then she’ll never be satisfied, forever toying and always disappointed. By the end Humbert has grown into a lunatic, paranoid and crazy-eyed at even being away from her. Kubrick makes this all happen in economic one-takes, like when Quilty obsessively calls Humbert and the phone’s cord stretches across the room like a noose.

And for movies so largely about sexuality, they each end on a frigid note. Zeigler brings Bill into his billiard room to carefully explain out everything that’s happened over the last 24 hours. When Humbert and Lolita meet again after years of being apart, she plainly explains she’s married, pregnant, and even has glasses that make her look remarkably like her mother.

Dramatically, both of these scenes are something of a let-down, or an anti-climax. Kubrick has tied up all the loose ends in a way that’s largely less interesting than everything building up to them in either film. And yet these endings are by design. They remind of the after-effects of sex, the letdown that occurs outside of the moment.

Cruise and Mason are both weirdly perfect casting choices. Mason is so hapless and bland as Humbert, and you can see him straining in just about every moment to tolerate Charlotte and her friends. He gets some broad strokes of physical comedy as he so delicately and quietly tries to set up a rollaway cot in his hotel room while Lolita is sleeping. He never seems comfortable in his own shoes, and Kubrick is able to mold him like clay in his hand.

Cruise in “Eyes Wide Shut” is something of a revelation. Here is an actor who tries so hard in every role to be liked, who gives his all and never melts into the role, namely because he’s Tom friggin’ Cruise. Kubrick isn’t blind to Cruise’s celebrity, and the performance he elicits from Cruise forces him to be a blank slate and a pretty face. Cruise is so cool and confident with all the women he encounters and all the opulence and luxury he places along his spiritual journey, but you can see him squirming. You can see how thoughts of his wife’s illusory betrayal – which he imagines in hazy, black and white flashbacks – constantly weigh him down as he tries to keep a straight face.

The one performance in “Lolita” that doesn’t really fit into “Eyes Wide Shut’s” equation is Peter Sellers as Quilty. Sellers is so good in every moment he’s on screen. It rivals his work on Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove”, but here he gets to play so many more characters and in so many different ranges. First he’s the effete and cultured dramatist creating sparks with the hotel’s bellhop and admiring the “lilting, lyrical” quality of Lolita’s name, all the while keeping a demonic looking muse in tow who never speaks a word. Then he gets the opportunity to turn in something of a Brando impression, sheepishly rattling off friendly pleasantries as a way of toying with Humbert’s mind. He displays a remarkable cadence in every word he says. Just watch him blinking and fiddling with his glasses; even Kubrick can’t look away.

All these performers are hot commodities in movies that have no desire for their sex appeal. Their casting is as much a tease as Nicole Kidman’s back, and though it’s not sexy, it’s remarkably scandalous.

The best scene in “Black Mass”, a biopic on the life of Boston’s notorious gangster James “Whitey” Bulger, is when a naïve, young waif of a girl is picked up by Bulger and her stepdad after spending the night in jail. Bulger grills her on exactly what the police asked of her and how much she knows. What’s exciting about the scene is not the fear of what Bulger might do but how oblivious she is to all the danger she’s in.

The best scene in “Black Mass”, a biopic on the life of Boston’s notorious gangster James “Whitey” Bulger, is when a naïve, young waif of a girl is picked up by Bulger and her stepdad after spending the night in jail. Bulger grills her on exactly what the police asked of her and how much she knows. What’s exciting about the scene is not the fear of what Bulger might do but how oblivious she is to all the danger she’s in.

It’s Christmas Eve in a sun-drenched Hollywood. Sin-Dee Rella is a transgender prostitute back out on the block after a month in prison. Her first stop is Donut Time, a divey hangout that’s pure LA. Her best friend and fellow trans-prostitute Alexandra thinks they’re celebrating. Sin-Dee’s pimp boyfriend Chester has been cheating on her while in prison, and not with anyone, but with some “fish”, their clever way of saying that bitch has a vagina.

It’s Christmas Eve in a sun-drenched Hollywood. Sin-Dee Rella is a transgender prostitute back out on the block after a month in prison. Her first stop is Donut Time, a divey hangout that’s pure LA. Her best friend and fellow trans-prostitute Alexandra thinks they’re celebrating. Sin-Dee’s pimp boyfriend Chester has been cheating on her while in prison, and not with anyone, but with some “fish”, their clever way of saying that bitch has a vagina.

At this point even a revisionist version of Sherlock Holmes has grown stale. The character has become so ubiquitous, with its own resurgence in the last 10 years, that anyone who thinks they’re genuinely putting a new spin on the character is likely trying to pull one over on everyone, and Holmes himself would be the first to call their bluff. The Robert Downey Jr. version of Holmes in the Guy Ritchie films may have been a wacky street tough, but those films might’ve actually veered closest to the original Arthur Conan Doyle creations than anything.

At this point even a revisionist version of Sherlock Holmes has grown stale. The character has become so ubiquitous, with its own resurgence in the last 10 years, that anyone who thinks they’re genuinely putting a new spin on the character is likely trying to pull one over on everyone, and Holmes himself would be the first to call their bluff. The Robert Downey Jr. version of Holmes in the Guy Ritchie films may have been a wacky street tough, but those films might’ve actually veered closest to the original Arthur Conan Doyle creations than anything. We’ve grown used to the darkness. We’ve come to expect films to not have everything plainly visible and bright on camera, to see shadows and shades of color and light in the way we experience the world naturally. We’ve also come to see our heroes and our stars to make themselves look ugly, to hide in the shadows, to transform themselves, and to help make our viewing experience something other than natural, something disturbing and unusual.

We’ve grown used to the darkness. We’ve come to expect films to not have everything plainly visible and bright on camera, to see shadows and shades of color and light in the way we experience the world naturally. We’ve also come to see our heroes and our stars to make themselves look ugly, to hide in the shadows, to transform themselves, and to help make our viewing experience something other than natural, something disturbing and unusual.

It’s a long-running debate as to whether movies can actually have an influence over people to the point that it gets them to act. Movies inspire people, but do they get people to get out of their chairs and vote, or change the world, or convince them to be a better person?

It’s a long-running debate as to whether movies can actually have an influence over people to the point that it gets them to act. Movies inspire people, but do they get people to get out of their chairs and vote, or change the world, or convince them to be a better person?

The indie drama “Z for Zachariah” is a post-apocalyptic sci-fi in name only. Movies such as this year’s “Ex Machina” or the horror film “The Babadook” have played with genre as their setting to tell what is essentially a contemporary story. The scene and the plot are merely set dressing for a bigger parable.

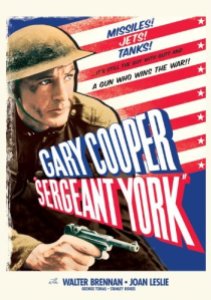

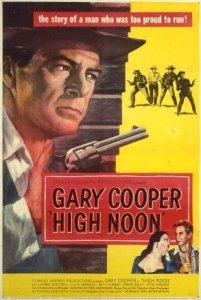

The indie drama “Z for Zachariah” is a post-apocalyptic sci-fi in name only. Movies such as this year’s “Ex Machina” or the horror film “The Babadook” have played with genre as their setting to tell what is essentially a contemporary story. The scene and the plot are merely set dressing for a bigger parable. Gary Cooper’s Will Kane wears a black cowboy hat throughout “High Noon”. The fashion choice is by design. He’s a hero, but by the end his victory is hollow. The town’s people he has sworn to protect have all left him for dead, for various reasons, and when he’s finally fulfilled his duty, he retires out of disgust, not achievement. In the film’s final moments Cooper wordlessly casts his “tin star” to the ground and rides off on a cart with his newlywed wife Amy (Grace Kelly in her first role). For a movie about a man who nobly puts loyalty to his job ahead of loyalty to his family, it’s more bitter and callous than inspirational.

Gary Cooper’s Will Kane wears a black cowboy hat throughout “High Noon”. The fashion choice is by design. He’s a hero, but by the end his victory is hollow. The town’s people he has sworn to protect have all left him for dead, for various reasons, and when he’s finally fulfilled his duty, he retires out of disgust, not achievement. In the film’s final moments Cooper wordlessly casts his “tin star” to the ground and rides off on a cart with his newlywed wife Amy (Grace Kelly in her first role). For a movie about a man who nobly puts loyalty to his job ahead of loyalty to his family, it’s more bitter and callous than inspirational.