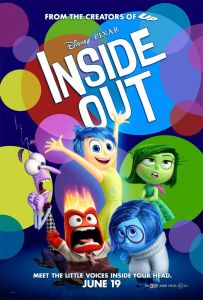

As adults, we use stories to explain to our kids how the world works. We have fables that teach kids etiquette, or why the planets revolve around the sun, or why we celebrate holidays. Pixar has managed an incredible feat (and it’s hardly the first time) by creating an entire ecosystem of ideas, mechanics and colors to help explain the most complicated aspects of our minds.

As adults, we use stories to explain to our kids how the world works. We have fables that teach kids etiquette, or why the planets revolve around the sun, or why we celebrate holidays. Pixar has managed an incredible feat (and it’s hardly the first time) by creating an entire ecosystem of ideas, mechanics and colors to help explain the most complicated aspects of our minds.

“Inside Out” is a movie about emotions and filled with them, but it’s really a portrait for who we are and how we function. Across their 15 films, Pixar has made a good handful of sheer classics, and “Inside Out” is among them. But Pete Docter’s film is groundbreaking because it may be the first to reach us on such an intimate, fundamental level.

What goes on inside your head? That’s the first question “Inside Out” asks and it’s a question that starts at birth. Riley (Kaitlyn Dias) is born, and with her first waking thought is Joy (Amy Poehler). Joy is a bright yellow sprite with short blue hair and eyes as big as her heart. She presses a button inside baby Riley’s mind and makes her smile. As Riley grows, more emotions emerge to work together and compete for control of Riley’s central control panel. First is Sadness (Phyllis Smith), a round blue ball of depression who literally brings down anything she touches. Fear (Bill Hader) is a skinny purple bug dressed in plaid helping Riley avoid tripping on cables or getting into trouble. Disgust (Mindy Kaling) is a stylish green drama queen averse to broccoli. And last is Anger (Lewis Black, naturally), a short red hot head in business casual attire who loves traffic, talking back to dad and complaining about San Francisco pizza.

For each memory and moment in Riley’s life, a colored ball coded to each emotion is created with a brief video clip memory, stored in “headquarters” during the day and then shuttled off to a massive array of shelves signifying long term memory. There, little sanitation workers dispose of phone numbers, U.S. presidents and more to make way for newer memories. Meanwhile, a small collection of “core memories” defines the islands of personality that make up Riley (if psychologists have said that our traits are in some way “connected”, Pixar has animated that idea literally). When Sadness accidentally turns one of Joy’s core memories blue, the two scramble to fix it and end up separated from headquarters and the ability to make Riley happy or sad. It all coincides with Riley’s disappointing move away from Minnesota to California and gradually leaves her interests, personalities and feelings crumbling away.

The factory-like mechanics of “Inside Out” are not unlike the Scream factory Docter envisioned in “Monster’s Inc.”, in which our emotions and how we process them keep the world moving. But Docter and co-director Ronaldo del Carmen have fun with every interaction and every moment of a human’s life. Not one line or image passes in front of Riley’s eyes that does not dictate a quick-witted reaction from one of our five little balls of emotions. It’s a movie that literally makes good on the expression that someone’s emotions have taken over. In a dinner table conversation between Riley and her parents, her father’s own team of workers launch into a war room, and putting his foot down has all the gravity of turning two keys to launch a nuclear sub.

And yet thematically, “Inside Out” feels closest to “Toy Story”. The anthropomorphic emotions have given their lives to making Riley happy and creating memories that shape who she is, and as she grows into becoming a teenager, her moods and her need for memories that made her a joyful kid are no longer needed. Joy and Sadness come across Bing Bong (Richard Kind), Riley’s discarded imaginary friend now wandering the far reaches of her mind hoping to one day be remembered.

Often without much exposition, Docter helps convey through colors and cleverly constructed puns (the arrival of a “train of thought”) and analogies the inner workings of the mind from dreams, the subconscious and abstract thought. There’s an incredible sequence that plays with the film’s animation worthy of one of Pixar’s daring animated shorts, in which abstract ideas transform Joy and Sadness into surreal, cubist shapes and eventually two-dimensional drawings. The sequence works as a goofy action set piece, but kids and adults alike can understand the external real world implications these actions have on Riley’s mind.

Some of Docter’s most poignant ideas are perhaps a bit more common than the film’s ingenuity and perceived originality give it credit for: sadness as much as happiness shape who we are and what we remember, and as we grow, even our emotions grow more complex. But it’s not the surface level emotions and ideas that make “Inside Out” such an incredible tearjerker. It’s the complete package of vivacious animation, exuberant humor and sheer imagination that help us better understand these feelings and make this film so human both inside and out.

4 stars

Boxing movies looked

Boxing movies looked

While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”.

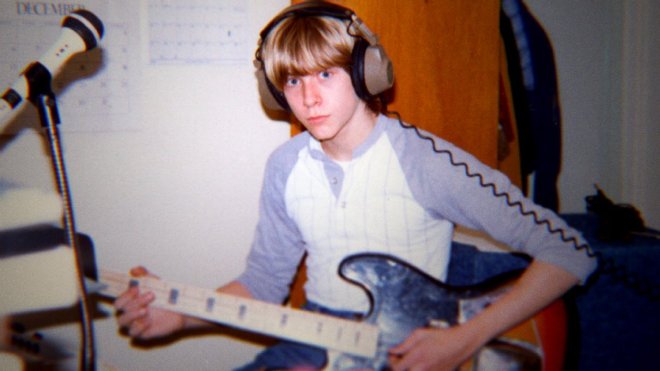

While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”. As a biopic, “Love & Mercy,” the story on the life of Beach Boys singer Brian Wilson, is a bit unusual. It passes over their surf pop rise to stardom in the early ‘60s in just the credits sequence. It jumps forward and backward in time to when Brian was both a young and middle-aged man on a whim. At times Bill Pohlad’s film is as deeply spiritual and scatterbrained as its subject.

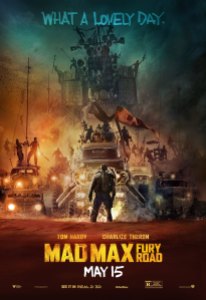

As a biopic, “Love & Mercy,” the story on the life of Beach Boys singer Brian Wilson, is a bit unusual. It passes over their surf pop rise to stardom in the early ‘60s in just the credits sequence. It jumps forward and backward in time to when Brian was both a young and middle-aged man on a whim. At times Bill Pohlad’s film is as deeply spiritual and scatterbrained as its subject. “Mad Max: Fury Road” is insane. It is batshit crazy. In a blockbuster age when CGI superheroes battle untold hoards of robots, monsters and aliens in a chaotic blur, there are just about no modern action movies that are purely mad.

“Mad Max: Fury Road” is insane. It is batshit crazy. In a blockbuster age when CGI superheroes battle untold hoards of robots, monsters and aliens in a chaotic blur, there are just about no modern action movies that are purely mad.

The exuberant pop of John Lennon’s lyrics on The Beatles’ “Help!” masked just how hurt Lennon really was. If only people had actually listened to the words.

The exuberant pop of John Lennon’s lyrics on The Beatles’ “Help!” masked just how hurt Lennon really was. If only people had actually listened to the words.

Marvel has been branding their Cinematic Universe in such a way that each subsequent film teases the next, and all seem to be building to something. “Avengers: Age of Ultron” should be that moment, but it doesn’t feel like the culmination of all that’s come before. Worse, it doesn’t even feel like an “Avengers” movie.

Marvel has been branding their Cinematic Universe in such a way that each subsequent film teases the next, and all seem to be building to something. “Avengers: Age of Ultron” should be that moment, but it doesn’t feel like the culmination of all that’s come before. Worse, it doesn’t even feel like an “Avengers” movie.