Daniel Craig and the new James Bond left a campy-sized hole in the hearts of many an action movie lover. The films became so polished, so good and even so plausible that while no one was clamoring for a throwback to Pierce Brosnan ice palaces and invisible cars, there’s a sense that spy stories could be a little less serious.

Daniel Craig and the new James Bond left a campy-sized hole in the hearts of many an action movie lover. The films became so polished, so good and even so plausible that while no one was clamoring for a throwback to Pierce Brosnan ice palaces and invisible cars, there’s a sense that spy stories could be a little less serious.

Enter “Mission: Impossible”, which five entries in has shed its TV adaptation roots and finally taken Bond’s place on the franchise throne. Previously the “MI” series has been a malleable Tom Cruise vehicle: a Hitchcockian thriller in the hands of genre stylist Brian De Palma, a visual showcase in the hands of John Woo or a dense conspiracy caper in the hands of J.J. Abrams. The fourth film, “Ghost Protocol”, was so delightfully cartoonish (in the hands of none other than Pixar’s Brad Bird making his live-action debut), that even dangling Tom Cruise off the tallest building in the world was not the most outrageous part.

So what is ironically fresh about the latest and fifth entry, “Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation”, is that Director Christopher McQuarrie isn’t trying to reinvent the wheel. The film has not taken on yet another new life in the hands of a new director but has found a comfortable groove that combines the best of all four previous films.

The most notable trait of course must be Tom Cruise, who continues to impress and prove why he’s a bankable star despite never once setting foot in superhero spandex or body armor. In purely Bond fashion, Cruise opens “Rogue Nation” with an incredible set piece detached from the plot of the main film. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt leaps aboard a taxiing plane and hangs on for dear life even after the plane takes off.

And that’s Cruise’s career in a nutshell: trying so hard and still able to hold tight against all odds even as every young teen star takes flight.

Here Cruise’s Ethan Hunt undergoes the Mel Gibson in “Lethal Weapon” treatment, being suspended from the ceiling and beaten and tortured, only to acrobatically crack some skulls and escape. He’s on the run after coming across an agent he believes to be the head of The Syndicate, Solomon Lane (Sean Harris). The Syndicate is a shadow organization made to destroy the IMF, and which Hunt believes was behind several global accidents he and the IMF were been unable to avert.

Lane’s frail, crippled tone behind glasses, a German accent and a short haircut make him sound like a man struck by lightning as a child. He’s a convincing ghost, and one of the franchise’s more memorable villains, if still behind Philip Seymour Hoffman from “MI:3”.

But the IMF is also facing a challenge from the CIA and their operation head, played by Alec Baldwin. The CIA is in denial that any Syndicate even exists, and the IMF’s biggest lead is a double agent named Ilsa (Rebecca Ferguson) who they first encounter attempting to murder a German chancellor.

It’s enough spy mumbo jumbo to keep the wheels moving and not too much to overwhelm the story in Macguffins and pseudo-science jargon. And the help of returning cast Simon Pegg and Ving Rhames continue to keep things light and tongue-in-cheek.

Because part of what makes “Rogue Nation” so refreshing, and for that matter all the “Mission: Impossible” movies, is how outlandish and oversized the film’s various set pieces can become, and yet are never once CGI maelstroms. One scene takes place in the backdrop of an opera in Vienna, and to say it’s magnificent, musically edited, and operatic is an understatement. Then there’s an underwater scene where Cruise has to hold his breath for three minutes while avoiding rotating gears and security blocks. It’s preposterous and near impossible to describe or rationalize, but in 2015 it’s more memorable than any horde of disposable robots.

These are traditional action movies after all, but when Bourne has gone gritty, the “Fast and Furious” movies have grown into their own superhero films, and John Wick has gone downright minimal, it’s nice to see that Ethan Hunt’s missions still look impossible.

3 ½ stars

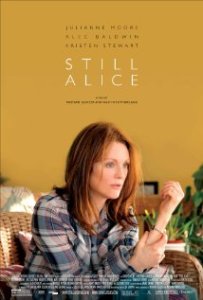

Though most fictional movies are not trying to be documentaries, there’s a desire we crave for authenticity in characters, storytelling and habits. To make a truly “authentic” movie about a woman suffering from a disease or disability might not be much of a movie at all. People grow old and sick, and those affected try to adapt and move on.

Though most fictional movies are not trying to be documentaries, there’s a desire we crave for authenticity in characters, storytelling and habits. To make a truly “authentic” movie about a woman suffering from a disease or disability might not be much of a movie at all. People grow old and sick, and those affected try to adapt and move on.