In this country during every sporting event, there is a moment reserved for the armed forces who have served this country. It could be a tearful commercial for beer, insurance, cars, anything, or it could be a standing ovation for two veterans during halftime. They sacrificed their lives, did their job, and that’s all we as a nation ask of them.

In this country during every sporting event, there is a moment reserved for the armed forces who have served this country. It could be a tearful commercial for beer, insurance, cars, anything, or it could be a standing ovation for two veterans during halftime. They sacrificed their lives, did their job, and that’s all we as a nation ask of them.

To ask anything more of our military or to question how they do their job goes against America’s values in the 21st Century. To suggest that they did something that’s out of line with what’s good for the country or what’s good for others around the world is tantamount to treason. Blame the country, blame the system, blame the terrorists, but don’t blame the troops.

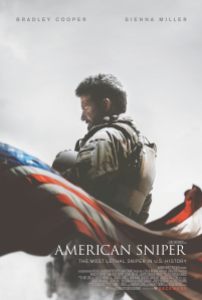

When we hear of a soldier like Chris Kyle, he’s not just a veteran or a hero; he’s a legend. Kyle was credited with over 160 kills as the most lethal sniper in American history. After four tours in the Middle East as a Navy SEAL following the attacks on 9/11, Kyle lived to tell his story in the book that became Clint Eastwood’s “American Sniper”.

Having not read Kyle’s book or known the man, I cannot comment on his character. “American Sniper” depicts Kyle’s life work as a soldier with all the valor and respect anyone in this country would be likely to give him.

And yet the portrait Eastwood offers of Kyle (Bradley Cooper) is a soldier who killed methodically, who showed no remorse for his assassinations, who brought himself to kill children as a result of his work, who labeled his victims “savages”, who placed his need to protect other soldiers above his own family, and who showed disdain for loved ones who expressed uncertainty at the work they were doing. I look at “American Sniper’s” Chris Kyle and see a flawed person, perhaps someone who shouldn’t be called a legend so willingly.

Yet Eastwood’s film is not so ambiguous. Kyle’s fight is against evil and his goal is to protect soldiers at all costs, all of which is a necessity as part of this job. Eastwood even crafts a cinematic device in the form of a single villain named Mustafa. He was an Olympic gold medalist in sniping from Syria, but here he’s a ruthless assassin who can pick off Americans from a mile away, never speaking a word and only seen sitting by a phone spinning a bullet as he awaits troop movements. He’s the embodiment of pure malevolence and Kyle’s ultimate rival, and he must be stopped.

Depending on which side of the political spectrum you sit, this may be more than enough justification for total war against terrorists or it may be a gross misappropriation of humanity outside of America. It’ll give you an idea of the horrors of war, but it may either fill you with pride for the work of brave men overseas or leave you uneasy at what they did there.

Perhaps Eastwood doesn’t need to pick sides. In “American Sniper” he leaves politics out of the equation altogether, and though there are enough naysayers within the military’s ranks to question the pursuit of glory and violence, he doesn’t vilify Kyle’s actions or suggest that he should feel bad for the body count he amassed.

What “American Sniper” provides is perspective. It gives insight into the effects of war on soldiers in a way many other films have succeeded at or failed at to varying degrees. And it best of all shows how a man like Kyle could choose war over his family. If “American Sniper” doesn’t make a bold statement of purpose about war, it at the very least tells a story and offers Kyle’s point of view with powerful, engrossing, classical storytelling. Eastwood proves he’s an old pro capable of stark action and emotion that will move everyone regardless of politics.

The film’s most revealing scene comes early during Kyle’s childhood. At the dinner table after a schoolyard brawl, Kyle’s father explains that all people are sheep, wolves or sheep dogs; people are either blind to the evil in the world, committing evil or sworn to protect the world from it. This philosophy guides all of Kyle’s actions and his motivation to engage in four separate tours despite the objections of his wife, and Eastwood doesn’t question this idea or view it with ambiguity. But who are the sheep dogs to pick out the wolves? Is there no middle ground between a dog and sheep? And does the sheep dog have the right to eliminate all the wolves, regardless of the flock?

This analogy thankfully doesn’t return in “American Sniper” to overstate a point, but those who do raise objections to war are often in the background. Kyle spots his brother going home after a tour, jaded and confused at what he’s done. Another close friend killed on the battlefield has his mother read a letter about the misguided pursuit of glory at his funeral. When his wife Taya (Sienna Miller) asks what he thought, Kyle says it was the letter that killed him.

With Kyle so resolute, it’s a shame then to see “American Sniper” so one-sided and to deny the Muslims depicted in the film as anything other than monsters. In each case of Kyle engaging directly with the Arabs who live in this war torn region, Eastwood flips the encounter into something more debasing. In the first, the man demands $100,000 for information on the whereabouts of a known terrorist. In the second, the man offers the Americans a feast, but does so only as a ruse. Kyle’s suspicion uncovers a stockpile of weaponry meant to kill them. The aforementioned Mustafa does not say a word, only murders. And Kyle frequently refers to those he kills as savages. After witnessing a woman and child brandishing a grenade meant for American tanks, Kyle says, “That’s an evil like I’ve never seen.” It’s here that the troubling sheep dog mentality rears its head, and Eastwood makes it feel as though he’s banishing evil from the world instead of killing people, innocent or otherwise.

In comparison, one of Eastwood’s best cinematic efforts was a pair of films that managed to show both sides of World War II, “Flags of Our Fathers” and “Letters to Iwo Jima”. The more patriotic “Flags” followed Americans who questioned the image sent back to the states after the battle at Iwo Jima, and “Letters” offered added depth to the Americans’ Japanese combatants and why they felt they needed to commit figurative or literal suicide as a natural expression of war. “American Sniper” lacks that counterpoint, framing much of Kyle’s story in flag waving terms that don’t sit well considering the violence on display.

Rather, “American Sniper’s” depth lies on the home front. Eastwood recognizes that there’s a torn dilemma between where home really lies for a soldier like Kyle, with his family of a wife and kids or his family of SEALs. The gravity of Kyle’s choice to do four tours lies in knowing what he’s leaving behind and how he rationalizes that he’s really protecting his family. Kyle’s wife Taya begs him to be human again, but it’s a touchingly realized moment when she realizes he’s not fully “here” when his mind is at war. If Eastwood fails at giving us the effects of war across international boundaries, he succeeds when crossing marital boundaries.

And yet the strength of “American Sniper” still does rest on the battlefield. When Kyle is seen sniping, Eastwood takes us into Kyle’s mental zone, focused to the point that time passes quickly in the background and that he can kill tirelessly without fanfare. It’s harrowing stuff always photographed clearly and crisply. Few directors outside of Eastwood have the ability to communicate a war shootout with such clarity.

Matching Kyle’s mental zone is Bradley Cooper, firmly in the prime of his movie star charisma and talent as an actor. It’s hard to imagine another actor fitting into Kyle’s combat boots, and Cooper takes Kyle’s focus to scary places. Sienna Miller likewise does strong work and brings much needed pathos to the film’s home front scenes.

After watching “American Sniper”, I’m still unsure about the real Chris Kyle’s heroics. Much has already been made about whether his depiction is accurate, and political proponents on both the right and left have sought to either champion or vilify Kyle to make a statement. But Eastwood above all has captured a powerful story with a character at the center who could be a legend, but is at the very least human.

3 ½ stars