In Andrey Tarkovsky’s “Stalker”, three men leave their desolate reality and enter The Zone, a verdant yet isolated slice of nature that breathes, changes, evolves and punishes those who don’t respect it. The men are in search of a mysterious room rumored to grant wishes to any who enter.

In Andrey Tarkovsky’s “Stalker”, three men leave their desolate reality and enter The Zone, a verdant yet isolated slice of nature that breathes, changes, evolves and punishes those who don’t respect it. The men are in search of a mysterious room rumored to grant wishes to any who enter.

To reach it however, the men aren’t braving obstacles or challenges, but revealing themselves to the higher power and unseen hand that watches over The Zone.

They pass through a sinister sewer, with metallic crunches accompanying every careful step. The camera tunnels behind the lead man and follows him shell-shocked for agonizing minutes. When he reaches the end, he gives up his only form of protection, a pistol, and makes himself entirely more vulnerable. He then descends a staircase into a room flooded with water, baptizing himself as he comes out the other side. And in a new chamber full of odd sand dunes, he collapses and bares his soul as though crossing a desert. The Zone has let him live for this long. “Yes, but why not forever”, he asks, tormented that he has escaped death but still not found solace or eternity. Finally, standing just on the precipice of the room capable of granting his inner most wishes, he adorns himself with a crown of thorns.

The spiritual and religious symbolism in “Stalker” is unspeakable, and yet the film takes a 180 in tone. People are shallow. The world is bleak. Solace is hopeless. Like Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” before it, “Stalker” is a gripping and tense sci-fi full of atmosphere and danger, but it profoundly grapples with themes of humanity and spirituality. It poses a fairly cynical idea that a room capable of granting all of humanity its innermost wishes is something of a paradox. “Unconscious compassion is not ready for realization.”

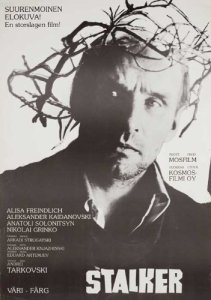

The film begins in a world so awash of color and life that it looks as though the apocalypse has struck. The opening shot creepily peers in at a sleeping couple, with the camera inching through barely open doors in a filthy room. Everything in this world is dank, with stagnant pools and junk scattered everywhere. The first man we see is a Stalker (Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy), who helps shuttle paying customers to The Zone to care for his wife and sick daughter.

His two passengers to The Zone are the Professor (Nikolay Grinko) and the Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), who each seem at odds with one another as they debate the concept of truth in a bar. “While I am digging for the truth, so much happens to it that instead of discovering the truth I dig up a heap of…pardon, I’d better not name it,” the writer says.

The Zone is well guarded, and Tarkovsky stages some expert, stealthy tension as they slink through this labyrinth of slums guarding the entrance. They reach a trolley that will take them to The Zone, and after several long takes of the back of the riders’ heads patiently awaiting this forbidden place, the camera smash cuts into color.

This “Wizard of Oz” effect though is the exact opposite of not being in Kansas anymore. For the Stalker, The Zone is home. It’s full of ruin and death of those who have failed to reach the Room before, but it has a beautiful solitude. Rather than take the direct route to the entrance and risk being punished, Stalker leads Professor and Writer on the scenic route through caverns, fields and watery tunnels.

Tarkovsky keeps his camera at a distance. They’re treacherous and observant, but also strangely calming and hinting at a higher power. He shoots through doors and grates that act as portals and amp the nervous tension of being watched and judged by nature. We never actually see the danger, but we constantly sense it.

Better yet, we believe. “Stalker” is a film about faith, and it forces its characters to become pious, to give up their human boastfulness and certainty in favor of tapping into their innermost feelings. Tarkovsky stops the film several times for dreamy prayers and meditations that preach such piety. Here’s one that speaks volumes:

Let everything that’s been planned come true. Let them believe. And let them have a laugh at their passions. Because what they call passion actually is not some emotional energy, but just the friction between their souls and the outside world. And most important, let them believe in themselves. Let them be helpless like children, because weakness is a great thing, and strength is nothing. When a man is just born, he is weak and flexible. When he dies, he is hard and insensitive. When a tree is growing, it’s tender and pliant. But when it’s dry and hard, it dies. Hardness and strength are death’s companions. Pliancy and weakness are expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.

Other films that consider similar themes of faith and humanity stop only at channeling The Book of Job. And others still could extract a slick action thriller out of “Stalker” (based on the Russian novel “Roadside Picnic”) but leave the spiritual ideas on the table. “Stalker” goes further and has an ending that grapples with the paradox of achieving our deepest desires and knowing the feeling of immortality or the afterlife. It’s not a cathartic ending, but in the film’s final shot we witness Stalker’s daughter resting her head on a table. The scene is in color, and she has taken a little of Stalker’s color with her. She moves a glass with her mind until it falls off the table, and we’re left with just a little hope at something more powerful lingering in our world.