A woman is carefully studying one of Margaret Keane’s paintings of a waif like child with big eyes in a state of poverty and despair. She says, “It’s creepy, maudlin and amateurish. And I love it.”

A woman is carefully studying one of Margaret Keane’s paintings of a waif like child with big eyes in a state of poverty and despair. She says, “It’s creepy, maudlin and amateurish. And I love it.”

Tim Burton’s “Big Eyes” tells the story of Margaret Keane, but his film only meets the last two criteria of Margaret’s paintings. “Big Eyes” feels like a standard biopic placed in a maudlin setting, but it lacks the surreal, absurd, cartoonish character that has defined even some of Burton’s worst films. In the process, he loses the humor, wit and even political point of view necessary to make good on Margaret’s story.

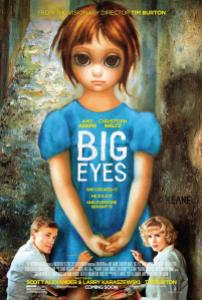

Margaret Keane (Amy Adams) was a painter in the ‘50s and ‘60s who attained enormous success with her “Big Eye” paintings. All portraits of children, the moody sketches were pure kitsch and possibly art, but regardless, they sold like hotcakes. Reproduced countless times over, it became possible to buy a Keane at your local grocery store.

The only problem was that Margaret saw none of the attention for her work. Her husband Walter (Christoph Waltz) convinced her that the work would sell better if people thought that it came from a man, so he took credit for himself and eventually became an established artist hobnobbing with Andy Warhol and being torn to shreds in the New York Times. Once the lie and Big Eye empire were established, Walter convinced Margaret that if she were to ever reveal the truth, the whole enterprise would come crashing down. Margaret remained silent for years until a circus of a legal battle in which Walter still claimed he was the sole painter of the Big Eyes.

Immediately Margaret’s story brings to mind women’s rights and what it means to be a female artist either in 1960 or 2015. Burton however doesn’t seem to have a political bone in his body, and he comments as little about the present as he does the past, seeking only to tell Margaret’s story in traditional terms.

Burton also misses an opportunity to take the courtroom material and make it truly outrageous. At one point Walter acts as both his own prosecutor and witness, leaping up and down from the stand with aplomb and play-acting the stereotypes he’s seen on old Perry Masons. Waltz executes the scene with charm, but he’s an actor who can go further, and Burton doesn’t ask him to, playing the moment mostly straight and not technically for laughs. The historical details of Margaret’s story are seedier and more outrageous than Burton even thinks to portray, something that seems peculiar given just how kooky and dark Burton can make established properties like Batman, Alice in Wonderland or the soap opera Dark Shadows.

Even bigger questions of truth, forgery and art seem to linger as untouched subjects. Something like “American Hustle” worked the idea of forgery into the very fabric of its storytelling. Even one of Burton’s best films, “Ed Wood”, explored the idea of whether even the worst art can still be called genius. Why can’t “Big Eyes” make a bigger claim about the nature of art, and how even kitsch and sentimental pap can still move people in a way that makes it art?

Keane’s art was all of those things but seemed weird enough to suggest there was an artist under those layers of canvas. “Big Eyes” amounts to little more than its surface level appeal.

2 ½ stars