Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.

Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.

But Altman is a director of character and dialogue. For as complicated as the story gets, we never lose track of the people and the moods at its core. If “The Long Goodbye” has earned comparisons to Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Inherent Vice”, it’s because Thomas Pynchon’s prose matches Altman’s attention to detail in the richness of his characters that color every moment. Altman’s signature conversational style and his theatrical cast of characters feel right at home with the thorny, pulpy stuff of a Raymond Chandler novel, as the menagerie of free-loving nudists, Jewish mobsters, Hemingway-grade drunkards, sinister psychiatrists and play-acting toll booth attendants wonderfully wrap us in Chandler’s twisted yarn.

In order to appropriately convey a place and a time Altman knew so well, he had to update the iconic character Philip Marlowe into the 1970s, transforming him from a hard-nosed detective played by the likes of Humphrey Bogart into a smart-talking loser whose body language and dress sense couldn’t be more out of place in this more modern world.

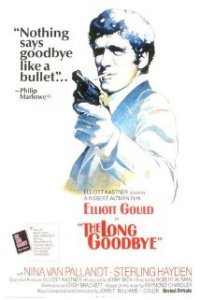

Altman enlisted Leigh Brackett to write the screenplay, who previously had a hand with another Raymond Chandler novel, 1946’s “The Big Sleep”. And Elliott Gould steps into Marlowe’s shoes and suit, a brilliantly pathetic and smarmy performance that finds Marlowe pitifully attempting to pass off a different brand of cat food to his cat.

For a while, “The Long Goodbye” is a lark. Topless women are making brownies next door to Marlowe’s apartment. When cops come and ask him about his friend who has disappeared, Marlowe is an utter smart-ass. When he gets pulled in for questioning, he sees the grocery clerk who insulted him at the store because he has a girlfriend and doesn’t need a cat. The two exchange quick words, and it’s another sign of how fully developed these characters are, however momentary they appear on screen. And when the detectives question Marlowe, he’s managed to put on a healthy coating of black face just to further play the fool.

In that moment, things get serious on a dime. In a few overlapping words and a jumble of point of view shots, Marlowe’s friend Terry, whom he just drove to Mexico to avoid suspicion, is dead. The stakes and suspicions have been raised. Someone is dead, the cops think it’s a suicide, but characters that we’ve met only in passing or not at all have enough depth to make us believe not all is right.

Altman is well known as a wonderful storyteller, but “The Long Goodbye” is good evidence of Altman as the brilliant visual stylist. When the reveal of Terry’s death is made clear, we get it from behind one-way glass, a coldly effective way to up the dramatic tension. When he’s calling Terry’s neighbor to follow his suspicions, the camera tracks in on Marlowe ever so slowly. The pace is measured and laid back, befitting of a comedy, but the urgency and curiosity is there. And when Marlowe first questions Terry’s neighbor Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt), Altman elegantly illustrates in one unbroken shot and no dialogue what another director would make all too obvious. Marlowe turns Eileen’s face toward the camera, revealing the bruised, drunken abuse of her husband Roger (Sterling Hayden), all without an additional close-up or point to call attention to it.

So much of “The Long Goodbye” is filled with these modest thrills and twists. Moments of great conflict, like when a mobster smashes a Coke bottle across his girlfriend’s face, or when Eileen spies Roger walking out into the ocean, are remarkably memorable. But all of them are executed minimally in the way that Altman does best. The latter doesn’t even utilize John Williams’s recurring “Long Goodbye” score motif. It’s not slow cinema waiting for a surprise or action cinema building tension. Altman has allowed his characters to stew in a pot, bubbling with humor, emotion, peculiarities and finally excitement, and what their actions mean in the grander scheme of a “plot” is almost beside the point.

That’s not to say “The Long Goodbye” doesn’t have an incredible story and a perfectly summed up finale. But its charms are in how it breaks apart the rigid confines of the mystery genre and makes a movie that’s equal parts funny and fascinating. It’s like the cat food Marlowe’s trying to pass off to his cat: what’s inside feels different and strange for those who haven’t tried noir or Altman, but the label surrounding it still makes a wonderful package.