One of the most heart-rending tracks on Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bookends” album is “Voices from Old People”. Not even a song, it’s a collection of elderly, frail, shrill voices not directly clear but echoing throughout the room. It’s ambient, natural sound reverberating off the walls, with overlapping discussions about death and life and everything in between. One woman speaks about how she still sleeps on her half of the bed long after her husband has passed. It’s lonely, devastating, and endlessly fascinating.

In the sprawling halls and rooms of the once great mansion Grey Gardens, Edith and Little Edie Beale’s voices travel throughout their home in much the same way. In just the way Albert and David Maysles allow us to listen to them chattering about their former glories, we get a poignant sense that the people we’re observing and the home in which they live are relics. The Beales are a pitifully saddening portrait long past its prime, in desperate need of restoration. Perhaps most painful of all is that in “Grey Gardens”, they still present themselves as though they’re an elegant museum piece.

In “Grey Gardens,” “Salesman,” and “Gimme Shelter” the Maysles Brothers captured life and people in a way that they felt somewhat pained. All of their movies could at times be funny, exciting, insightful, and intimate, but there’s a sense of pain that runs through all of them, that these are somewhat lonely or wounded people.

Albert Maysles passed away at the start of March. His documentary style that he adapted with his brother has grown somewhat out of fashion. Werner Herzog and Errol Morris would be more aggressive and cynical. Many others would be more topical or political. And others still doing portraits and slice of life movies would move away from the “Fly on the Wall” type of documentary filmmaking.

But the Maysles still hold incredible influence and have their fingerprints on many facets of contemporary documentary filmmaking. In the case of “Grey Gardens”, both Albert and David are actually quite present. Little Edie speaks and even performs for the camera. It heightens the idea that she’s a socialite and debutante, simply lighting up once the camera shines in her face.

The story of the Beales isn’t told during “Grey Gardens” but is simply introduced. Both Big and Little Edie are relatives of Jackie O, President Kennedy’s wife. They had been thrust into the public spotlight when their home at Grey Gardens estate was threatened to be condemned. Landlords had discovered the wretched state in which the two lived, under filthy conditions and crumbling disrepair. Jackie O personally helped them remain in the home, but two years later, the Maysles pick up with them to see how they’re faring.

Suffice it to say things have not improved. In the Blu-Ray reissue by the Criterion Collection just released, we have a pristine look at the filth, grime and mess littered around their home. Bugs are crawling on the walls in numerous frames. Little Edie leaves an entire loaf of white Wonder bread for raccoons and cats to pick from. When they have guests, they drink champagne from Dixie cups. They’re a hideous wreck.

But the Maysles aren’t here to necessarily judge or ascribe a reason as to why they feel unwilling to improve their horrid conditions or leave. We’re allowed to make that assertion on our own, and both Big and Little Edie need barely any prodding to speak their mind and make a case for their pitiful delusion. Together they bicker about tiny details and do so in a high-pitched shrill befitting a decade well before the ‘70s. And despite the mess of their condition, Little Edie still seems concerned with décor, wall patterns and fashion choices. We never see Little Edie without her shawl, and she deliberately makes choices to wear frumpy skirts inside out with mismatched blouses.

The Maysles get a look at old photos of the two, and it’s impossible to imagine that the brimming debutantes photographed are the same people. In providing that backwards look, it would be easy to say the Beales are simply mentally ill, unable to cope with the present. But the Maysles are smart enough to get intimate with the details of Big and Little Edie’s conversations. Little Edie expresses a desire to leave, to do more and to relive so many opportunities she has missed out on, but the Maysles make it clear that the two together thrive on their bickering and their reminiscing of the past. They bring out the best and worst in each other, and though they’re keeping a dangerous illusion alive, they also maintain their charm and poise.

Modern reality shows like “Hoarders” or shows highlighting the garish and the ugly are only interested in those extremes. The Maysles saw the Beales and could’ve condescended. Instead they made a portrait with nuances and shades.

They were possibly the only documentarians to do the same for a bunch of rock stars, The Rolling Stones. Looking at the Maysles visual technique, they’re an unusual bunch to be filming a rock documentary complete with concert footage. During the Stones various performances, the camerawork is without many of the usual flourishes that are typical in the genre. In fact, they appear transfixed with Mick Jagger’s face in tight close ups, arguably not a bad subject.

But what they do call attention to in their live performances is just how ragged and raw the Stones were back in their heyday. Today the Stones live show is so polished, complete with pyrotechnics, orchestras and choirs, but the Maysles demonstrate that they were once just five guys on stage with a lot of energy.

They also bring to the film the inspired idea to sit the Stones down and show them the footage. “Gimme Shelter” documents the band’s struggle to stage a free concert out in California. So many kids were expected, the location had to be altered numerous times, and the logistics just seemed impossible. 300,000 arrived in 80,000 cars lined for miles along the road. But it became really controversial once security arrived. The Stones hired the Hell’s Angels biker gang, who were largely uninterested in protecting the band or others. The Maysles simply observe the mayhem, and the way they shoot it, without comment or fanfare, truly makes it seem like a cultural event (they did the same when documenting The Beatles arrival in New York). One gang member pulls an entire motorcycle from underneath a group of bodies in the crowd. And when things really go wrong, the Maysles are there to confront and humble the Stones with the consequences of their performance.

The Maysles even brought this humble, observational quality to a short they did titled “Meet Marlon Brando”. Filmed at a press event in 1966, it’s easy to see why Brando was not just a great actor, but a true movie star. The Maysles edit out the substance of the press questions and focus on Brando’s charm and irreverence. We see him here as handsome, flirtatious, and best of all, unexpected in everything he says. On the whole, “Meet Marlon Brando” is not an essential moment for the Maysles but a neat novelty to see Brando in an unusual position.

But just two years after, the Maysles did film their first essential documentary, “Salesman”. The simplicity of this story with these characters would be almost unheard of today, better reserved for a magazine article or indie film. But in four wandering salesman, the Maysles capture one of the toughest lifestyles of the ‘60s as well as some of the American hardship and culture of the time.

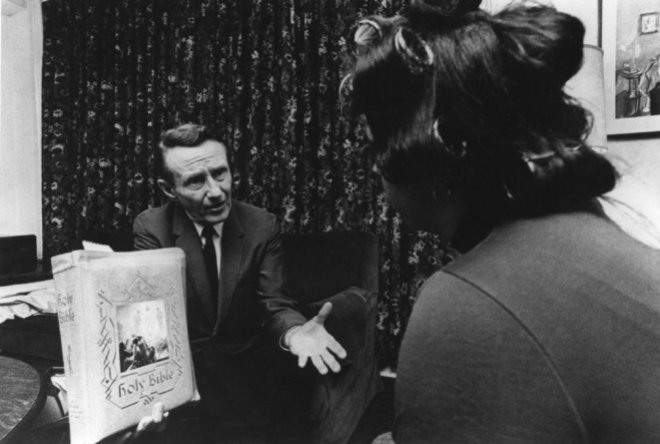

The Badger, the Gipper, the Rabbit and the Bull. All four salesman have their own styles, experience and level of success as we see each try and hock some expensive Bibles for nearly $50 each, which would be a lot even in 2015. The Bibles are massive, filled with ornate lettering and images and perhaps completely unnecessary, but sell them they must. The Maysles never comment on whether this is a worthy endeavor (even in the ‘60s, this way of life already seems to be fading), but view the men themselves as upstanding.

We relate to them in a curious way. “Salesman” vaguely reminds of the profane dialogue found in “Glengarry Glen Ross”, and surely Jack Lemmon could play one of these men in a movie, but they’re largely pitiable. They’re charming and slick, vaguely racist, and perhaps unflinching, even when certain clients seem to be hiding home and financial troubles, but we feel for them when time and again they hit a wall when failing to close. They’re stuck driving around suburbs in Florida, away from any wives or children we never see and whom they may not even have.

The Maysles are given surprising access into people’s homes and truly do feel like flies on the wall, but that’s not to say “Salesman” is any less intimate or understanding. They bring that rare quality of touch and nuance to all four of these films, and no one did it better.