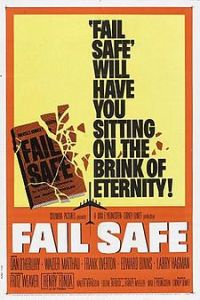

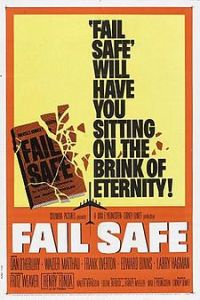

Sidney Lumet’s “Fail-Safe” is a forgotten masterpiece released the same year as Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove”.

My generation never grew up with the fear of imminent destruction. The media raves about the threat of ISIS to America, and we were born into an age where our country had experienced the worst attack on American soil, but the Millennials like me never knew the feeling of the Cold War and the threat of a real super power on the brink of total nuclear war and annihilation.

My generation never grew up with the fear of imminent destruction. The media raves about the threat of ISIS to America, and we were born into an age where our country had experienced the worst attack on American soil, but the Millennials like me never knew the feeling of the Cold War and the threat of a real super power on the brink of total nuclear war and annihilation.

For that reason, Sidney Lumet’s “Fail-Safe” struck a particularly unusual chord. From 1964, it’s the stepchild to Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove,” with virtually the same plot but none of the irony or grim satire, and due to a lawsuit, it was kept on a shelf until after “Dr. Strangelove” left theaters and became the defining Cold War movie. The film bombed at the box office and was received as camp as a result, and now “Fail-Safe” is widely unseen, but ranks among Lumet’s masterpieces.

“Fail-Safe” is worlds more than a Kubrick clone or a Cold War movie without a sense of humor. It’s a grim and at times calmly nihilistic depiction of politics, bureaucracy and technology. Superbly acted, tensely directed and haunting to look at, it’s less a political commentary than a horror story of a system gone wrong and the world gone to hell as a result.

The plot that leads to doom is simple, but always feels more complicated as it’s happening. Before the times of long range missiles, fighter jets still needed to carry bombs to their targets. American pilots survey an area for suspicious enemy movement, and if they reach a critical Fail-Safe point, they can receive an order via a closed circuit box instructing them to attack. The system is designed to be fool-proof and account for all possibilities, but a mechanical malfunction leads one team of pilots to set on an attack course to Moscow. Believing these orders came directly from the President, the pilots are not to turn around or verify the attack via radio, fearing the possibility that America is already under attack and unable to communicate or that the President’s voice could be impersonated. “Fail-Safe” plays out as a real time race of negotiation with the Russians, strategizing and attempts to shoot down the rogue planes.

While the last plot twist seems like an implausible, fatal flaw, Lumet uses it as a strategic plot device. In such a system where safeguards are put in place, it’s the systems, the policies and the people obligated to obey them that results in tragedy. And the fears that put these systems in place are not aimless. There’s a constant fear of surveillance and technology as to what the Russians are truly capable of, and it’s these presuppositions that lead to the worst.

“Fail-Safe” heightens the pulse of the Cold War tenfold, and it conveys the many nuanced debates and worst case scenarios with eloquence and suspense. The generals in the Pentagon debate the possibility of a limited war, and how with calculated casualties victory can be achieved. While there are vocal naysayers pleading for the prevention of war at all costs, a Pentagon advisor played wickedly by Walter Matthau eggs on the logic behind an attack. He’s a calculated mastermind not unlike Dr. Strangelove who imagines that the only survivors of nuclear war will be convicts in solitary confinement and file clerks. The way Matthau plays the role, seemingly disconnected from the rest of the grounded cast, his political theory ranges from outlandish to scarily accurate.

That nuance is just one virtue Lumet brings to “Fail-Safe.” His characters across the board are not one-dimensional, over eager or seeking bloodlust. They’re flawed bureaucrats trying to find the best case scenario and discovering it to also be the worst. And Lumet carries that nuance into the war room and to the emotional stakes. In one pivotal scene, American General Bogan (Frank Overton) is revealing the location of the rogue fighter jets to a Russian general so they can be shot down and that disaster can be averted. As they talk and fear failure, Bogan is given a file with the general’s picture and one of his family. It’s a poignant, minuscule touch that makes “Fail-Safe” plain brilliant.

But the film is also striking as a film on the cusp of a revolution in Hollywood filmmaking. Lumet incorporates the same claustrophobic feel he brought to “12 Angry Men,” but the sparse settings, imposing low angles and even some repeating jump cuts make it feel daringly unlike anything in Old Hollywood. Two of the film’s best performances and most impressive cinematography come from the scenes with Henry Fonda as the President and Larry Hagman as Buck, his translator. Confined to a sparse bunker for the entirety of the film, Lumet stages incredible monochromatic close-ups that put these two at odds and have them staring down the camera with immense gravity. It’s amazing how much tension Lumet draws from such economy.

And yet “Fail-Safe’s” ending is so powerfully sickening that it makes me question its necessity. The President’s twist is something I will not reveal, but it feels outrageous and impossible even for the stakes Lumet has raised. Sure enough, the consequences are immense and the conclusion is nightmarish. I’m trying to think of another film that has ended in such a way, one with as much of a bleak, devastating outlook as this.

To symbolize such an outcome as a natural possibility and the only rational choice in this circumstance might be too great a scene to depict without any irony in the way “Dr. Strangelove” did. “Fail-Safe” ends with a disclaimer from the Army that none of the technological glitches that occurred are truly possible, and the real cold irony is that Lumet is inadvertently saying they’re wrong. Does such an end justify the horrific means it took to arrive here? “Fail-Safe” is such immensely powerful storytelling and filmmaking that in a time separated from “Dr. Strangelove,” it certainly would.

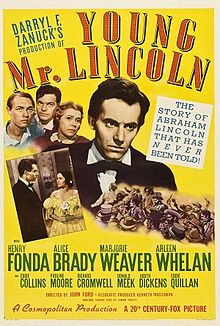

“You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.” Henry Fonda said in a 1975 interview that he only played Abraham Lincoln because John Ford (who else) “shamed” him into doing it. “You think it’s The Great Emancipator huh? He’s a young, jack-legged lawyer from Springfield for Christ sake!”

“You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.” Henry Fonda said in a 1975 interview that he only played Abraham Lincoln because John Ford (who else) “shamed” him into doing it. “You think it’s The Great Emancipator huh? He’s a young, jack-legged lawyer from Springfield for Christ sake!” My generation never grew up with the fear of imminent destruction. The media raves about the threat of ISIS to America, and we were born into an age where our country had experienced the worst attack on American soil, but the Millennials like me never knew the feeling of the Cold War and the threat of a real super power on the brink of total nuclear war and annihilation.

My generation never grew up with the fear of imminent destruction. The media raves about the threat of ISIS to America, and we were born into an age where our country had experienced the worst attack on American soil, but the Millennials like me never knew the feeling of the Cold War and the threat of a real super power on the brink of total nuclear war and annihilation.