She’s as mad as hell and she isn’t going to take it anymore. Jodie Foster’s “Money Monster” (her follow-up to “The Beaver“) doubles as a media critique and a corporate screed folded into a small-scale thriller, and frankly it has just a few too many targets; “Network” meets “The Big Short” it’s not.

She’s as mad as hell and she isn’t going to take it anymore. Jodie Foster’s “Money Monster” (her follow-up to “The Beaver“) doubles as a media critique and a corporate screed folded into a small-scale thriller, and frankly it has just a few too many targets; “Network” meets “The Big Short” it’s not.

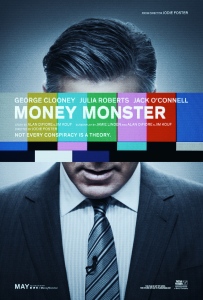

George Clooney plays his typical charming asshole, but this time channeling a Jim Cramer-type TV personality named Lee Gates. On his show, he makes stock tips with bells and whistles so ludicrous that his producer Patty (Julia Roberts) has accepted a job at another network and neglected to inform him. Because of the nature of the show’s stunts, a disgruntled New Yorker named Kyle (Jack O’Connell) manages to sneak onto set and hold Gates hostage with a homemade suicide vest, all while still broadcasting live. Kyle holds Gates responsible for telling his audience to invest in a company that just lost $80 million overnight due to a “computer glitch” and won’t stop until the company’s CEO (Dominic West) explains himself.

As Gates showboats with boxing gloves on the set of his show or draws voluptuous curves on an earnings graph, the movie starts to roll its eyes at itself and tacitly suggest that the sensationalism in today’s media could realistically result in such a hostage situation. But while Gates’s show resembles “Mad Money,” neither the terrorist scenario nor the Wall Street debacle necessarily feel ripped from the headlines.

Rather, “Money Monster” imagines how the world would react if such a circus took place on live TV. In between the cops plotting their rescue attempt and the corporate Communications Officer attempting to unravel the mystery of what happened to $80 million, Foster cuts away to random people watching TV in bars and coffee shops. Those in suits on Wall Street smirk and laugh, while others keep ordering drinks and playing foosball. To them it’s just another reality show.

The screenplay’s commentary (co-written by Jamie Linden, Alan DiFiore and Jim Kouf) has some interesting ideas, but flounders compared to the humanity Foster is able to wring from these characters. O’Connell’s character especially displays a lot of range, quickly moving from a deranged maniac with a manifesto to someone relatable and pitiable. And Clooney has to face the realization on live TV that his flashy personality and surface level charm may not be worth a thing.

If “Network” has become a classic, it’s because its sensationalized version of the media all came true. It has aged with shocking poignancy and clairvoyance. “Money Monster” may even be an entertaining drama, but when it hops on the soapbox and condemns a fishy stock market and fixed legal system, it already feels outdated.

2 ½ stars