“You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.” Henry Fonda said in a 1975 interview that he only played Abraham Lincoln because John Ford (who else) “shamed” him into doing it. “You think it’s The Great Emancipator huh? He’s a young, jack-legged lawyer from Springfield for Christ sake!”

“You’re crazy! I can’t play Lincoln. That’s like playing God, to me.” Henry Fonda said in a 1975 interview that he only played Abraham Lincoln because John Ford (who else) “shamed” him into doing it. “You think it’s The Great Emancipator huh? He’s a young, jack-legged lawyer from Springfield for Christ sake!”

We certainly do have this revered image of our 16th President, and yet the two biggest actors who have played him, Fonda and more recently Daniel Day Lewis, both played Lincoln with a sort of laid back aplomb. In their performances they made Lincoln into a great man by separating him from the esteem and the myth.

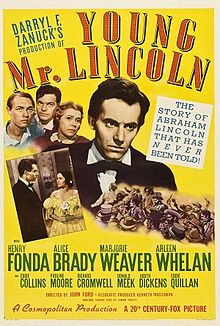

In “Young Mr. Lincoln,” which Ford cranked out in his seminal year of 1939 alongside “Stagecoach” and “Drums Along the Mohawk,” it’s immediately apparent that the image of Lincoln that Ford is going for differs from that of the stuffy politicians and bourgeois speaking in grand statements. He’s a proletariat homeboy who spoke calmly and plainly and won over the nation through his clear, honest demeanor and homespun wisdom.

Much of that credit certainly belongs to Fonda. Instantly he gives Lincoln a humble, trustworthy presence. It’s all in his tall and lanky body language. He leans on doorways and railings not unlike the iconic stooped perch he musters in Ford’s “My Darling Clementine, his poise and shoulders are lax, casual and he never has the need to truly boast or raise his voice. Look at one scene in which Lincoln, practicing as a young lawyer in Springfield, convinces two men who both want damages from the other to settle their case. He acts as though he’s telling them a story and lesson before revealing that he’s good at cracking heads, his eyes turning into icy spears as he does.

All the while Ford shoots Fonda at congenial, reassuring angles. Our first great look at Lincoln is a centered shot from chest height, just slightly glancing up at his sheepish face. Unlike the politician who spoke before him, Ford doesn’t frame Lincoln as some towering figure, but a relatable one. Lincoln’s words reached people on their level, and so does Ford’s film.

The story itself is a fictionalized version of one of Lincoln’s first court cases when he was a young man, not a president. Some out-of-towners get into a fight with a local brute, and when the man ends up dead, the town wants to lynch the two outsiders. Lincoln single-handedly stops the mob and agrees to defend the boys in a rousing and amusing courtroom drama. It’s complete with a few teases to his eventual wife Mary Todd and to his rival Stephen Douglas (a scene with John Wilkes Booth was cut from the film), but the film’s real charms lie in how Ford can capture the pulse of a community from this period.

“Young Mr. Lincoln” acts as a call for a more relatable leader, one who can subdue the fire of an angry crowd just through his words, but also one who will eat pies, split rails and cheat at tug of war, an average person who is in actuality extraordinary.