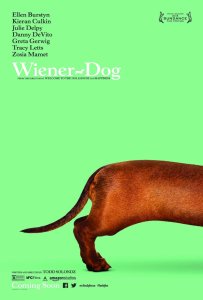

Always get the name of the dog. That’s a reporting tip to find that extra detail that your audience will remember. In Todd Solondz’s latest film “Wiener-Dog,” this little brown dachshund goes from being named Doody to Cancer between four separate owners, and each name seems to reflect something different about the quirky, strange people behind it.

Always get the name of the dog. That’s a reporting tip to find that extra detail that your audience will remember. In Todd Solondz’s latest film “Wiener-Dog,” this little brown dachshund goes from being named Doody to Cancer between four separate owners, and each name seems to reflect something different about the quirky, strange people behind it.

“Wiener-Dog” is an ensemble piece, much in the tradition of one of Solondz’s morose and squirm-inducing comedies such as “Happiness,” but Solondz drops the connecting threads that explain how this dog got from owner to owner pretty quick. He even includes a cute intermission of the dog walking in front of a green screen displaying locations across the country. It instead plays like four short films, and the varying tones between them give “Wiener-Dog” equal feelings of yearning and failure, satire and gross-out humor, and above all highs and lows.

The dog’s first owner is a young boy (Charlie Tahan) who names it simply Wiener-Dog. His wealthy parents (Julie Delpy and Tracy Letts) want him to be happy, but keep Wiener-Dog in a cage in the garage and talk about training it as a bleak way of breaking its will. Delpy delivers a hilariously tender talk to her son about spaying and neutering, in which one stray dog who went without getting spayed ended up getting raped, contracting AIDS and dying. It’s gleefully disturbing imagery, that is until at least Solondz quite literally drags our nose in shit, or more accurately, doggie diarrhea.

Whether you’ll enjoy Solondz’s sensibility to blend gratuitous humor and striking, deadpan cinematic style, in this case slow motion and classical music as he pans across the stained floors and carpets, is entirely subjective. Sometimes he holds these visuals just long enough to make it laughably uncomfortable, and other times his awkward distance gets the better of him, including a fairly ugly joke at the end that’s simply in bad taste.

But some of “Wiener-Dog’s” high points have little to do with the dog. Greta Gerwig, who’s perfectly perky and pathetic, plays Dawn Wiener, a veterinary assistant who runs off with the animal and names it Doody. She then agrees to leave her life and travel with a stoic, handsome drifter (Kieran Culkin) she knew from high school. This chapter has surprising depth, and even finds in Dawn some hope for a new beginning. Solondz killed off Dawn Wiener in one of his earlier films, “Palindromes,” and here he accomplishes an optimistic rewrite.

Then there’s Danny DeVito as the nebbish, no talent loser Dave Schmerz, a film school professor at NYU who can’t get someone to even look at his screenplay and doesn’t get any respect from his students. Solondz could’ve made a whole film about these snobby film students you’ll just love to hate. But DeVito’s solemn performance, him constantly straining for words and conviction, brings the film back to its themes of atrophy, depression and loneliness.

As for the film’s final chapter, a meeting between the elderly Nana (Ellen Burstyn) sporting gigantic black visors and a DGAF attitude and her granddaughter Zoe (Zosia Mamet) and artist boyfriend Fantasy (Michael James Shaw), it’s hard to know what to make of a scene so bizarre. These people may belong to another universe entirely, but it’s the ideal culmination to a film so amusingly erratic.

Where you stand on “Wiener-Dog’s” final gag may just determine how you feel about Solondz’s entire filmography. And while this isn’t Solondz’s best or worst, the film’s irreverence is made meaningful and special because of his awkward charms. If Solondz were going to make any movie about a dog, it’d be hard to imagine it working as well with anything other than this dog.

3 stars