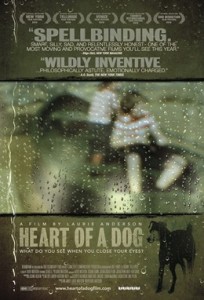

It’s been argued that the most experimental films are often the most realistic. In Laurie Anderson’s touching, lovely, thoughtful and spiritual visual essay “Heart of a Dog,” she approximates the inner workings of the mind through her language, animation and sound. Between delightfully twee anecdotes and more melancholy meditations on life, Anderson grapples with the notions of death and loss and goes deeper into these subjects than most traditionally fictional stories.

It’s been argued that the most experimental films are often the most realistic. In Laurie Anderson’s touching, lovely, thoughtful and spiritual visual essay “Heart of a Dog,” she approximates the inner workings of the mind through her language, animation and sound. Between delightfully twee anecdotes and more melancholy meditations on life, Anderson grapples with the notions of death and loss and goes deeper into these subjects than most traditionally fictional stories.

At a brief 75 minutes, the only real narrative Anderson has belongs to her late dog, Lolabelle, a terrier that eventually went blind. She blends the line of documentary and fantasy with stories that ascribe thoughts and emotions to her dog. In one early anecdote she and her dog are on a hike when vultures swoop down and try to grab Lolabelle. Suddenly the dog has become aware of threats from the sky when previously all she knew were the ants on the ground. In one of “Heart of a Dog’s” more strained analogies, Anderson likens this realization to her own thoughts following 9/11. But many more of her stories have fun giving Lolabelle anthropomorphic qualities, going as far as to have a dog POV camera on the New York streets or Lolabelle pounding on a synthesizer to create her “Christmas Album.”

Anderson’s husband Lou Reed died while making the film, and while he appears only briefly, that feeling of loss lingers throughout “Heart of a Dog.” Her images and her animations are delicate scrawls and wisps, gracefully patched together in a way that echo the colors we see when we close our eyes. Anderson says in the film these are “phosphenes,” the “eternal avant-garde movies and screensavers” we have in our minds. And this tone she strikes allows her to reach a feeling of grief without being cloying.

Anderson too has a soothing, comical and endlessly curious fascination to her voice as she narrates the images. “The limits of my language are the limits of our words,” she says, dancing around stray thoughts about Japanese dogs wearing clogs to making some more vaguely political insinuations.

At no point though do you have to share Anderson’s spirituality or politics in order to appreciate her reverie. “Heart of a Dog” is more of a guided meditation in film, a phrase that sounds a lot more inviting than an experimental visual essay.

3 ½ stars