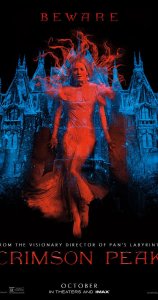

Guillermo del Toro is one of the few mainstream filmmakers with the vision and foresight to take craft, visuals and artistry into mind in his filmmaking. But since “Pan’s Labyrinth” he has yet to live up to his auteur reputation. “Crimson Peak” is del Toro taking a stab at more modest genre filmmaking, and while the film is bursting with colors, special effects and the finest in set design, Del Toro’s embodiment of them ranges from at best superfluous to at worst meaninglessly pastiche. “Crimson Peak” is horror and the macabre often for its own sake, and it plays more like two hours of concept art rather than a fully fleshed out film.

Guillermo del Toro is one of the few mainstream filmmakers with the vision and foresight to take craft, visuals and artistry into mind in his filmmaking. But since “Pan’s Labyrinth” he has yet to live up to his auteur reputation. “Crimson Peak” is del Toro taking a stab at more modest genre filmmaking, and while the film is bursting with colors, special effects and the finest in set design, Del Toro’s embodiment of them ranges from at best superfluous to at worst meaninglessly pastiche. “Crimson Peak” is horror and the macabre often for its own sake, and it plays more like two hours of concept art rather than a fully fleshed out film.

“It’s not a ghost story; it’s more like a story with a ghost in it,” says the film’s protagonist Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska). She echoes the first misnomer about “Crimson Peak”, which has been advertised not as a horror film but Gothic Horror. Yet del Toro is no stranger to traditional horror jump scares or shrieking attacks of strings on the film’s score. It only strives for Gothic horror in that it plasters old-fashioned kitsch everywhere.

The film’s color scheme of reds, yellows and blues seems constantly in conflict with itself. Allerdale Mansion, an English estate where Edith is swept away to by her new husband and sister in law Thomas and Lucille Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston and Jessica Chastain), is an impossible structure of pure malevolence. It has ominous cracks in the ceiling, endless corridors, and massive walls and staircases headed nowhere and only made to impose. Short of writing on the walls, “This house is evil” (wait! we’ve got ominous Latin inscriptions and looming portraits of their vicious mother), it even seeps a red clay ooze from the floor. Points if you can guess that symbolism.

Del Toro’s attention to detail doesn’t stop at his sets. He employs classical editing techniques like a pinhole shot to remind you this is old fashioned, quaint and thus even more sinister. The film opens with a fairy tale warning from Edith’s dead mother and is even bookended with a literal book opening its pages at the film’s open.

And yet del Toro’s style is all superficial. The camera doesn’t particularly move with grace and the set design does all the heavy lifting rather than the framing. Without this, del Toro’s technique and visual references smack of pastiche. The same style without substance claims have been saddled on other movie buff directors like Quentin Tarantino and Wes Anderson in the past, but “Crimson Peak’s” visuals don’t so much set a mood as remind you of one.

“Crimson Peak” concerns how Edith falls in love with Thomas, the mysterious entrepreneur from across the pond. Her father disapproves, but when he’s brutally killed in what is inexplicably thought to be an accident, Edith and Thomas marry and return to England. His intentions though may only be to fleece Edith of her wealth, and Thomas’s sister Lucille seems itching to dispose of her sooner.

But again, everything here is bleak and devilish from the onset. It’s a movie of secrets and ghosts with haunted pasts, but there are no real secrets to be had. The Sharpes’ intentions are so clear that we care little about what they’re hiding in their past. Chastain plays Lucille as so immediately cold and vicious to remove all doubt. She’s dressed out of place in blood red when we first see her, and after playing piano her fingers are crippled and vampiric. Every line of her dialogue is whispered and made to be an idiom with a hidden double meaning. Chastain isn’t bad, but she’s being directed to chew the scenery and play broad.

It’s because Lucille announces her intentions as in it for the money, but also the horror of it. del Toro is invested in “Crimson Peak” for the same reason, not to tell a story of love, ghosts or secrets, or “a story with a ghost in it” as Edith suggests, but to pay an overwrought ode to horror itself.

2 stars