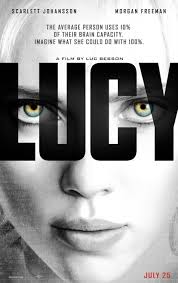

Luc Besson’s “Lucy” is a mad genius mash-up of “The Tree of Life”, “The Matrix” and “2001: A Space Odyssey”. Its script, concept and sheer disdain for rules or accurate science make it laugh out loud ridiculous, but in doing so it becomes purely inventive and cinematic. “Lucy” is about no limits via the power of your mind, and this film seems to have none. It’s a wacky blast of an action/sci-fi that in just 90 minutes simply doesn’t stop.

Luc Besson’s “Lucy” is a mad genius mash-up of “The Tree of Life”, “The Matrix” and “2001: A Space Odyssey”. Its script, concept and sheer disdain for rules or accurate science make it laugh out loud ridiculous, but in doing so it becomes purely inventive and cinematic. “Lucy” is about no limits via the power of your mind, and this film seems to have none. It’s a wacky blast of an action/sci-fi that in just 90 minutes simply doesn’t stop.

Scarlett Johansson plays Lucy, and her performance matches the alien precision, depth and control she brought to this year’s seriously weird “Under the Skin”. In it, Lucy is a clueless blonde tourist bullied by her new boyfriend into delivering a briefcase into a hotel. As she reaches the front desk, the boyfriend is killed, and she’s taken upstairs to a group of Japanese mobsters. They pressure her to open the case, fearing it may explode, and all the while, all too on-the-nose images of cheetahs stalking their prey intercut between the action. It’s obvious, overwrought symbolism but builds powerful energy into every moment.

Like Lucy, we’re totally in the dark. Besson makes it feel as though anything can happen next, and it does. After the case is opened, Lucy finds four packets of blue crystals that turn out to be a new drug. A junkie is forced to try the drug, he throws his head back in a conniption, laughs in Lucy’s face and subsequently has his head blown off. Lucy is then transformed into an unwilling drug mule, forced to carry the bag of drugs surgically placed in her intestines. Nothing’s happened yet and all ready this movie is bananas.

Cut to Morgan Freeman giving a lecture about how we only use 10 percent of our brain’s capacity. It seems completely random, and a seemingly odd moment to lay out the film’s bizarre premise and pseudo science. The natural images flashed during his presentation bring to mind some Terrence Malick movie in awe of the possibilities of the universe. It’s all token stock footage, but it’s made all the more unusual by their placement.

And in no time at all, Lucy is on the friggin’ ceiling. The bag of drugs gets released into Lucy’s bloodstream, unlocking additional parts of her brain that give her increasingly limitless telekinetic power. In a flash, she grabs a gun and murders her captors, inhales food and pulls a bullet out of her shoulder; she didn’t even notice it hit her.

As her brain capacity grows, so do her abilities and the movie’s zany possibilities. She can read Japanese, hear conversations from a mile away, absorb all the information of the Internet in minutes, recall fleeting memories of her time as a baby, take control of phones, TVs and computers, shape shift her hair and body and render an entire room helpless with a flick of her wrist.

Besson doesn’t stop to put rules in place on what Lucy can and can’t do. She just does. In the process Besson amasses a gigantic body count and has all the fun in the world doing whatever he pleases. It’s cathartic and exciting to see just how outrageous “Lucy” can get.

But Besson also doesn’t bother with a genuine backstory, melodrama or morality for Lucy that might slow the film down or muddle the ideas and possibilities he’s trying to explore. Besson instead relies on Johansson to convey a trace of humanity within her heightened state of mind. She plants a sudden kiss on a helpful detective, she musters a feeble smile to an old friend, and she finds a brief moment to call her parents and say how much she loves them.

“Lucy” actually charts similar territory as Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar”. They both make big nods to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001” in their visuals and themes, but “Lucy” does away with Nolan’s stodgy plotting and rules and conveys a sense of infinite possibility and a higher human understanding by actually showing us instead of telling us. This is what cinema is supposed to do, stoke the imagination through images and wonder. And not despite the goofy plot but because of it, “Lucy” is a gorgeous feast to watch, but you would’ve never guessed it would come in such an unusual package.

4 stars