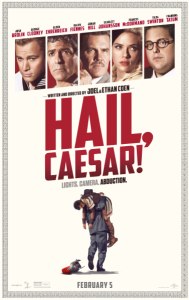

The Coen brothers’ “Hail, Caesar!” acts as a sizzle reel for all the classic Hollywood film genres the pair could’ve honored and lampooned throughout their career but never got the chance. It shows how the Coens might do a sword and sandal epic, a lush costume melodrama or even a Gene Kelly musical. But “Hail, Caesar!” is a movie about the future, a post-modern mish-mash of genres and styles that hints at where history will take cinema as much as it is a throwback. The Coens are having a lot of goofy fun but still manage a surreal, captivating art picture on par with many of their classics.

The Coen brothers’ “Hail, Caesar!” acts as a sizzle reel for all the classic Hollywood film genres the pair could’ve honored and lampooned throughout their career but never got the chance. It shows how the Coens might do a sword and sandal epic, a lush costume melodrama or even a Gene Kelly musical. But “Hail, Caesar!” is a movie about the future, a post-modern mish-mash of genres and styles that hints at where history will take cinema as much as it is a throwback. The Coens are having a lot of goofy fun but still manage a surreal, captivating art picture on par with many of their classics.

Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin) was a real VP and “fixer” in Hollywood up through the ‘50s, but here he’s an executive with the fictional Capitol Pictures, the same studio that employed Barton Fink. His job requires wrangling stars and getting films completed, and he’s the through line connecting all of “Hail, Caesar!’s” disjointed cinematic set pieces that traverse genres. Set during the 1950s, Capitol’s major prestige picture, also called “Hail, Caesar!,” is a story of Christ featuring the massive Hollywood star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney, playing a doofus as he so often does in Coen films). A pair of extras drug Whitlock on set, abduct him to a meeting of Hollywood Communists, and demand $100,000 in ransom.

Meanwhile, Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich, delivering a breakout performance) is a burgeoning Western star reassigned to a fancy production called “Merrily, We Dance.” He can’t really act to save his life, and he doesn’t gel with the loquacious, British thespian of a director Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes channeling Vincente Minnelli). It’s Doyle who becomes “Hail, Caesar!’s” unlikely hero instrumental in locating Baird.

“Odd” does not quite capture how perfectly weird “Hail, Caesar!” actually plays. No scene or gag feels cut from the same cloth. The Coens will stage an opulent aquatic ballet in the spirit of an Esther Williams/Busby Berkeley routine starring Scarlett Johansson as a mermaid starlet, with the kaleidoscopic colors and aerial shots at times recalling “The Big Lebowski’s” dream sequence, only to abruptly cut away and become a shadowy noir.

Even the Coens humor ranges from absurd to deadpan to modest to rapid-fire wordplay. There’s Tilda Swinton channeling Old Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper as not one, but two twin sisters, never on screen at the same time and each one-upping the other in terms of their readership. There’s the cleverly circular dialogue between a group of religious experts debating whether “Hail, Caesar!” will pass censors. And of course there’s Channing Tatum, who explicitly reminds everyone why he’s the contemporary Gene Kelly, donning a navy sailor suit and charming the hell out of the audience with a showy tap dance number.

Ehrenreich as Hobie Doyle is the real surprise, a baby faced dolt with a stoic, stilted demeanor. In one shot he performs a lasso routine just to pass the time, and his eyes barely emote a thing in a way that makes his act hilariously Buster Keaton-esque. And in a verbal showdown with his director Laurence Laurentz, a simple line reading, “Would that it were so simple,” becomes the film’s unusually outrageous centerpiece.

What do the Coens have to say with all this madness? If the set pieces seem cold, or if the individual sequences feel disconnected from the rest of the film, it’s the act of showing the movie’s seams that stand out. Between flashy wipe cuts and gorgeously artificial backlot sets, the color and visual design of “Hail, Caesar!” leap out at you. We recognize Hollywood as the beautiful forgery that it was, and we can appreciate the Coens’ tribute to the era in how they call attention to everything it stood for.

Hollywood was all of these things in its Golden Age, and in the subtext are Mannix’s internal malaise, the arrival of the H-bomb at Bikini Atoll, and the coming drama of the Blacklist. “Hail, Caesar!” does this period better than “Trumbo.” But it invokes the arrival of the near future, how genres would be blended and how the world would become less clear. “Hail, Caesar!” is a lot of movies rolled into one, but it captures the spirit of an era in a way very few films have.

3 ½ stars

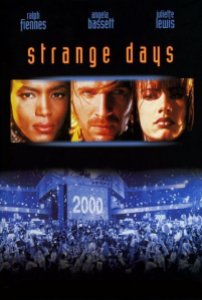

One might assume that a film set at the dawn of the new millennium and about the fear of Y2K might feel a hair dated. But while that aspect does, “Strange Days” touches on a subject that’s been more than prevalent in 2015.

One might assume that a film set at the dawn of the new millennium and about the fear of Y2K might feel a hair dated. But while that aspect does, “Strange Days” touches on a subject that’s been more than prevalent in 2015.