Do we really need another movie or show that reimagines old fairy tales? How many different ways can we tell the story of Cinderella? Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Into the Woods” first premiered in 1987, but since then the spirit of taking beloved childhood properties and twisting their meanings to play up the dark imagery and fables at their core has exploded into pop culture. It hardly seems new to suggest that the Little Red Riding Hood story has gross undertones of, perhaps, pedophilia or otherwise. Ooh, how sinister.

Do we really need another movie or show that reimagines old fairy tales? How many different ways can we tell the story of Cinderella? Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Into the Woods” first premiered in 1987, but since then the spirit of taking beloved childhood properties and twisting their meanings to play up the dark imagery and fables at their core has exploded into pop culture. It hardly seems new to suggest that the Little Red Riding Hood story has gross undertones of, perhaps, pedophilia or otherwise. Ooh, how sinister.

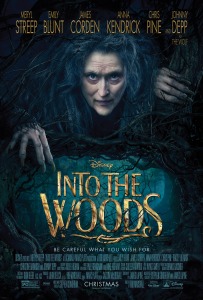

And yet here we have Rob Marshall’s live action film adaptation of “Into the Woods”, which reimagines the fairy tales yet again but has defanged them even further. Marshall’s film is hardly as subversive or as slyly perverse as its subject matter, either by Sondheim or Brother Grimm, suggests. And like all the worst film adaptations of Broadway stage musicals, it pays more lip service to the theater than it does to cinema. “Into the Woods” often looks cheap and visually uninteresting, stimulated only by some above average singing.

Sondheim’s story is a mash-up of several popular childhood fables, Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood and Rapunzel, all brought together by a baker and his wife (James Corden and Emily Blunt) who cannot conceive a child. They’ve been cursed by a witch (Meryl Streep) and can only break the spell by collecting four items, one belonging to each of the fairy tale characters. Their paths intersect in one of those frustrating cast numbers that look great when everyone is participating and moving on stage, but meander and jump around as a result of incessant film editing.

Streep is really the star of the show, going big and broad and bold in the way only she can and owning her songs. Constantly she’s stalking and hunching over with a grimace and dominating the screen. She’s only matched in hammy overacting by Chris Pine as Prince Charming, who may be both the best and worst part of the film. He has a so-dumb-it’s-amazing number called “Agony” in which Sondheim’s composition itself is dripping in self-aware swells, only enhanced by Pine nonchalantly brandishing his chest and tossing around his golden locks as though he were blissfully unaware of his masculinity.

Marshall however plays it mostly (ahem) close to the chest, allowing the actors to do all the heavy lifting. Say what you will about 2013’s ugly looking “Les Miserables,” but the film at the very least had a style. Some of the sets look flat out cheap, and by the film’s climax involving giants descending from the beanstalk, Marshall tries to pay homage to the original production by hiding them within the scenery, but it looks more like the budget simply ran short.

Only by “Into the Woods’s” end do the characters start to get a sense of depth as flawed figures. One song points the finger at every character and their intersecting mishaps, and it reveals themes of parenting, family, abandonment and more.

Surely Sondheim’s original production has its ardent supporters for this very reason, but Marshall just wants to put the musical on the big screen again. Hollywood has lamented the loss of popularity for the movie musical, but part of that decline might stem from only making films that can have a slavish devotion to a beloved source material. Put an original property in Marshall’s hands, and he’s talented enough to do more with what he’s done to Sondheim.

2 ½ stars