Richard Linklater was featured in a documentary with another famous director James Benning. The two were watching “Sweet Smell of Success” together, and 10 minutes before the end, as a random man speaks with Burt Lancaster, Benning made a casual joke saying, “And then we just follow that guy, right at the climax of the movie.” Linklater, who was just finishing editing “Slacker” thought to himself, “Uh oh, I just made an entire movie like that.”

Richard Linklater was featured in a documentary with another famous director James Benning. The two were watching “Sweet Smell of Success” together, and 10 minutes before the end, as a random man speaks with Burt Lancaster, Benning made a casual joke saying, “And then we just follow that guy, right at the climax of the movie.” Linklater, who was just finishing editing “Slacker” thought to himself, “Uh oh, I just made an entire movie like that.”

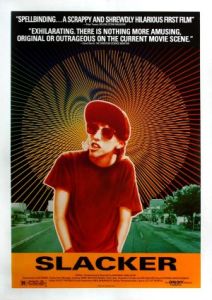

And I thought nothing happened in “Boyhood“. Richard Linklater’s “Slacker”, his first film, is strictly an experiment. It bucks narrative or protagonists altogether and simply wanders around Austin, Texas observing people, life and behavior. Since 1991, Linklater has coalesced this ploy into the most honest, thoughtful, introspective and emotional cinema he’s making today, from the walking and talking romances of “Before Midnight” to the documentary hybrid “Bernie“.

“Slacker” lacks these traditional narrative devices because Linklater wanted to make a point that audiences could relate to people not on story but on personalities, moments, events and the things we experience everyday. To say nothing happens is missing the point. A lot happens in every day; it’s just a matter of choosing which details to focus on, and what those details can tell us about ourselves.

Linklater lays out his thesis right up front, making a cameo in the backseat of a cab traveling from the train station. “Have you ever had a dream,” he asks, “where everything feels so life like, but nothing happens?” That’s “Slacker” in a nutshell, but for as lazy and uneventful as the actions of his characters, Linklater doesn’t rest on his laurels, and makes pains to think of these things profoundly. “Every thought you have is a choice you make, and they all become separate realities.”

It sounds merely like college psychology quad talk at first, but Linklater then deliberately avoids telling a story to make this point. A woman is hit by a car and is lying dead in the street. Someone says to call the police and help her, but instead of hanging around and learning to find out more about the woman or what happens next, Linklater goes out of his way to follow a passerby into his home. Later, a teenager is walking to his friend’s house, and an older man starts keeping pace with him and talking his head off about conspiracy theories. He’s allowed to ramble, and rather than confront him to stop and cause conflict, the teen arrives at his destination, the two carry on with their day, and we carry on with the next couple.

“Slacker” has an undeniable rhythm to these little observations, each one so nuanced and detailed in their momentary slices of life. Some of the people are funny and awkward (one woman offers two friends Madonna’s supposed pap smear, thinking it to be valuable), others are thoughtful and philosophical (“Perhaps human beings aren’t meant to be happy. We’re always enslaving ourselves”), and others still are ironically morbid (“The next person who passes us will be dead within a fortnight”).

Linklater spends individual moments with a mentally challenged person, a hapless loser, an annoying hipster activist, a conspiracy theory weirdo, a lazy homebody, and kids who have discovered a way to get Coke out of the vending machine for free. Like “Boyhood”, these characters feel developed enough that we could spend an entire film with any one. But this is cinema, and life is endlessly more fascinating when we take the time to look around.