Justin Simien’s “Dear White People” plays like a Millennial’s “Do The Right Thing.” It’s extremely smart but insufferably self-aware and overly ambitious, expressing an exhausting need to check every box of racial injustice and semantics in America with a talky, motor-mouthed screenplay. The film grapples with interesting ideas of identity as it ties not just to race but to gender and sexuality among young people, but it doesn’t explain why all the film’s characters have to be pretentious, intellectual, elitist snobs, an unholy mix of Spike Lee and Whit Stillman.

On an Ivy League campus, Sam White (Tessa Thompson) is a mixed-race revolutionary with a radio show entitled “Dear White People,” where she criticizes white people who only have one token black friend or will date a black guy just to piss off their parents. Sam’s loaded language sparks sharp divisions among her Black Panther-esque acolytes and a house full of cocksure, white comedy writers led by Kurt Fletcher (Kyle Gallner), the University President’s son. In a surprise twist, Sam wins a house election over the incumbent Troy Fairbanks (Brandon P Bell), son of the school’s Dean (Dennis Haysbert). Their rhetoric, politicking and class dynamics on the college campus all escalate to an offensive party and race war teased at the start of the film, a scene that echoes “Do The Right Thing’s” intense rioting.

All the film’s dialogue gets so provocative and racially charged that it’s impossible to think Simien loaded the screenplay on accident. His characters too, even Sam, who the film describes as if “Spike Lee and Oprah had a pissed off baby,” are caricatures, exaggerated in order to comment broadly on our constructions of race and identity dynamics.

Simien poses thoughtful questions. What does it mean to “keep it 100” or to be true to your blackness? Eventually “Dear White People” peels back the layers of its characters and exposes them as frauds. Sam isn’t really Malcolm X, but her ability to speak her mind and embrace a righteous attitude has allowed her to find an identity. “Are you trying to be black enough for black kids or white ones,” one character poses to “Dear White People’s” neutral observer, a nerdy and gay journalist named Lionel (Tyler James Williams). That he struggles for an answer proves how complex these characters and these issues are.

And yet that exaggerated line between satire and reality often gets crossed, with Simien’s visual style further underscoring the racial dividing lines and the film’s aggressive tone. All the white people in the film are shot to look as though they came out of a university catalog, and Simien plays with quick wiping reverse shots to show that white and black people are at the opposite sides of an invisible line. He even takes time to editorialize, with an army of black students shouting directly at the camera how Tyler Perry movies promote stereotypes.

Some of this is fun and funny, but “Dear White People” gets overstuffed with its assortment of characters, including one (Teyonah Parris) who’s superficially trying to get on a reality show and become a star, as well as a subplot about student journalists who may just be using Lionel’s blackness as a way to get an editor position with The New York Times. It’s almost insulting how much the movie name drops, with Fletcher casually tossing off names of blogs like Gawker and Buzzfeed to illustrate just how smart and connected everyone on this campus is.

“Dear White People” is entirely made up of those too cool moments. It’s self-aware and smart to a fault, overlooking a more plausible central character in Lionel in favor of the more sensational Sam and muddling the line between satire and simply inflamed rhetoric.

As a straight white guy, “Dear White People” was made to get in my face and shake up my perception. But does it have to be “on” all the time?

2 stars

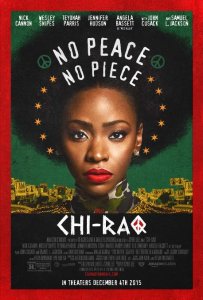

No movie this year is as bold-faced opinionated and timely of a political statement as Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq.” That’s because movies are rarely this topical, this aggressive or this urgent. The film is littered with names of African Americans the media has been shouting for months, it has numerous hashtag ready catch phrases, it stops the film for a sermon that is essentially a vicious op-ed, and it declares up front that “This is an EMERGENCY” in giant, flashing red letters.

No movie this year is as bold-faced opinionated and timely of a political statement as Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq.” That’s because movies are rarely this topical, this aggressive or this urgent. The film is littered with names of African Americans the media has been shouting for months, it has numerous hashtag ready catch phrases, it stops the film for a sermon that is essentially a vicious op-ed, and it declares up front that “This is an EMERGENCY” in giant, flashing red letters.