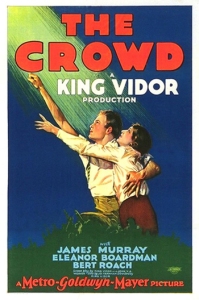

Has any single image in film history better captured the idea of conformity and order than the endless rows of identical desks in a vast office building in King Vidor’s “The Crowd”? Shot on a slant and tracked overhead to infinity, it’s one moment of many that display 1920s New York City as a futuristic, even surreal cityscape representative of all the world’s uniformity and ceaseless rat race. Vidor films at towering low angles that give New York such gravitas and immense presence, from skyscrapers that look like temples and the glistening lights of Coney Island that look heavenly.

Has any single image in film history better captured the idea of conformity and order than the endless rows of identical desks in a vast office building in King Vidor’s “The Crowd”? Shot on a slant and tracked overhead to infinity, it’s one moment of many that display 1920s New York City as a futuristic, even surreal cityscape representative of all the world’s uniformity and ceaseless rat race. Vidor films at towering low angles that give New York such gravitas and immense presence, from skyscrapers that look like temples and the glistening lights of Coney Island that look heavenly.

Vidor’s film has inspired countless artists, with the desks alone cropping up in Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment,” the Coen bros. “The Hudsucker Proxy” and Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil.” But rather than a satire like those films, “The Crowd” is a steep melodrama that manages to run the gamut of the human condition. It feels universal and innocent even as the film’s bleak melancholy sinks in.

Released in 1928, “The Crowd” is one of the last silent films of the early era of cinema (with the exception of some Chaplin stragglers). Like “Sunrise” the year before, Vidor had reached the peak of what was capable with silent filmmaking, the camera sweeping, the set design stylized and the lighting dreamy, all before talkies took over Hollywood and tied the camera down again for several years. Look at an early shot in the film, the camera angled down a flight of stairs that both illuminate and cave in on a boy slowly creeping up to learn his father has died.

Vidor uses these cinematic techniques to lend a macro sensibility of patriotism and worldliness to the micro story of a man hoping to amount to something. The generically named John Sims (James Murray) arrives in New York and hears from a passerby, “You’ve gotta be good in that town if you want to beat the crowd.” All John needs is an “opportunity,” and “The Crowd” is a film about how he’ll eventually conform to that crowd in order to make his own opportunity.

John’s attitude is one of entitlement, elitism and condescension, laughing at a man juggling to promote a billboard and believing with little evidence or work ethic that he’s better than the rest. Murray bites and licks his lip in a way that gives him a snobby quality and increasingly makes John unlikable. Within that characterization there’s a class dynamic at play. John’s in-laws are disapproving members of the bourgeois; they loath how he and his wife Mary (Eleanor Broadman) live in poverty beneath an El train.

John is detestable to the point that Vidor, in a pre-Code era, gets away with making the Sims’ Hollywood ending still fairly tragic, with society unwilling to mourn his family’s loss in one horrifying scene, and with John and Mary sinking into a sea of faces all laughing like buffoons at a vaudeville stage in “The Crowd’s” closing shot. “The crowd laughs with you always but will cry for only a day,” reads one ironic title card. John succeeds in the end, but not as a man who was so good he could beat the crowd, just join them.

“The Crowd” perhaps has not aged as well as some of the German Expressionistic silent films it was inspired by. But the film is a remarkable relic of 1920s New York prior to the Great Depression, and its influence is undeniable. In an age when Hollywood would seek to make escapist fantasies and popcorn entertainment, Vidor’s film had the audacity to stand out.