The marches at Selma, Alabama, the boycotting of buses in Montgomery, the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, the protests in New York: these aren’t just part of a “cause”. All this isn’t just “activism”. These are people’s lives at stake, and regardless of which side of the line you stand, blood has been shed both then and now.

The marches at Selma, Alabama, the boycotting of buses in Montgomery, the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, the protests in New York: these aren’t just part of a “cause”. All this isn’t just “activism”. These are people’s lives at stake, and regardless of which side of the line you stand, blood has been shed both then and now.

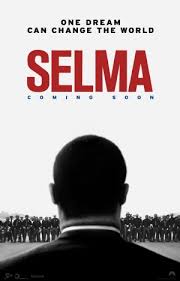

Lyndon B. Johnson called Martin Luther King Jr. just an “activist”, as it is depicted in Ava DuVernay’s “Selma”, saying he has one cause while the Presidential administration has 101. Much unnecessary controversy has been made over the accuracy of President Johnson’s relationship with Dr. King, but LBJ as he is seen here serves as a powerful symbol for why racial unrest in this country persists and why change continues to drag its feet.

“Selma” is a raw, emotional, and most of all modern drama that with modesty and dignity proclaims that injustice can’t be treated as just another issue on the table. Unlike other prestige biopics, DuVernay doesn’t for a minute allow melodrama into her film that would pretend that racism and violence are gone from this world. Her film is a poignant reminder of what was and how these people’s influences, both noble and ugly, still linger.

“Selma” focuses in on a small portion of Dr. King’s life work and is all the greater for it. DuVernay is able to dig into the thorny nuance of this particular event and draw modern parallels that ripple throughout the film. King (David Oyelowo) opens the film receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, and after a meeting with President Johnson (Tom Wilkinson), determines that help from the White House will not come soon enough. Their plan is to organize a rally in Selma and march all the way to the capital of Montgomery, nearly 50 miles away, in order to protest voting rights in the state.

King delivers a modest, yet powerful explanation of why voting rights for African Americans is so critical. Through fear and corruption of the courts, only two percent of blacks in Selma are registered to vote. Hundreds are then killed by the brutality of white cops and racist white residents, and all white juries led by a white judge fail to convict the killers of crimes because blacks cannot vote for the judge nor serve on the juries because they are not registered. This train of logic is crucial because a lack of convictions will certainly strike a chord with modern audiences.

And on the other side of the coin, we see repulsive logic that has most definitely carried its way through to 2015. George Wallace (Tim Roth), the then Governor of Alabama, explains to President Johnson that if blacks got the right to vote, they’d then want jobs, then schools, “then it’s distribution of wealth without work.” “Moochers” was not a term likely used in 1964, but DuVernay subtly makes her point about the way blacks are perceived today through this shocking lens to the past.

Civil Rights movies from period pieces (“The Help”) to the contemporary (“The Blind Side”) have framed their discussion of race through white people evolving, and it breeds melodrama and an assumption that things are for the better now. DuVernay doesn’t presuppose anything, and the politicking from King, Johnson and Wallace all remind of Spielberg’s “Lincoln” and the long, joint effort that went into creating change. She dodges the melodrama, keeps the film modest in scope and doesn’t lose any of King’s rousing words or messages.

DuVernay comes from the indie realm of filmmaking, and even “Selma’s” many moments of violence are visceral, in your face, raw, aggressive and all beautifully lensed by DP Bradford Young. There are fewer shots or moments of the movie dwelling on truly monstrous racists, and instead the bursts of violence throughout the film make all of “Selma” feel volatile. You can feel the tension as Dr. King begins to march thousands over Selma’s bridge out of town, and you can feel it as he or his cohorts sit in their homes, always in some form of danger from the hatred that surrounds them.

2014 was a year of great conflict, and of the movies the Academy Awards sought to recognize this year, many were biopics that focused on the heroics and struggles of the historians at the center. Of all of them, only “Selma” has captured the pulse of the nation yesterday and today.

4 stars